WIKIMEDIA COMMONS, IVAN ATMANAGARA

WIKIMEDIA COMMONS, IVAN ATMANAGARA

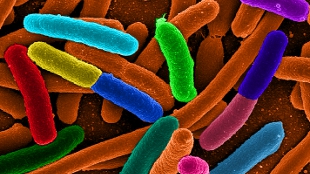

As evidenced by the E. coli outbreak in Europe earlier this year, which claimed dozens of lives and sickened thousands more, bacterial contamination of foods remains a significant problem. This outbreak clearly demonstrated that, despite recent improvements in technologies to detect and trace foodborne outbreaks, it will take continual advances in knowledge and techniques to prevent future epidemics.

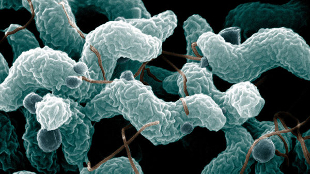

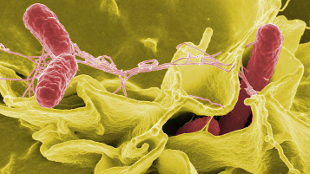

Each year, roughly one out of six Americans, or 48 million people, contract foodborne illnesses, according to estimates from the United States Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). The economic impact of foodborne illness is staggering, with a recent report from the University of Florida’s Emerging Pathogens Institute concluding that five leading pathogens —Campylobacter, Salmonella, Listeria monocytogenes, Toxoplasma gondii and norovirus — cost the nation $12.7 billion annually. But while it may seem like we’re experiencing more outbreaks than in the past, this perception merely stems...

In the mid-1990s, for example, the CDC instituted a program called PulseNet following a large E. coli outbreak in the western United States. A national network of public health and food regulatory agencies, including state health departments, local health departments and federal agencies, such as the U.S. Food and Drug Administration and the U.S. Department of Agriculture, are using common procedures to test bacteria from ill people and compare it to bacteria sampled from foods. Similarities identified help public health and regulatory officials determine whether an outbreak is occurring, and if so, where it originated and which way it’s headed. With PulseNet, outbreaks and their sources can be identified in a matter of hours rather than days. A recent National Biosurveillance Advisory Subcommittee (NBAS) report called for a similar effort worldwide to help recognize and respond to global threats, like the European E. coli outbreak, more quickly.

Furthermore, a number of food testing technologies developed by corporations in recent years are detecting lower levels of pathogens in less time, enabling contaminated foods to be more quickly identified and prevented from making it to market in the first place. DuPont Qualicon and BioControl, for example, have developed rapid tests that use polymerase chain reaction (PCR) to detect Salmonella and Listeria in about 24 hours. This is a dramatic improvement over traditional culture methods used two decades ago that took anywhere from four to seven days to return results.

Another test, developed by my colleagues at bioMérieux, detects low levels of Salmonella contamination in a one-step sample preparation, and delivers results in as little as 19 hours. The test, launched this past June, utilizes recombinant bacteriophage proteins from viruses programmed to identify and infect Salmonella. Because phages are extremely host-specific, they offer unrivaled sensitivity and specificity for detection and differentiation of bacteria from food and environmental samples. bioMérieux also has developed a phage-based test for the detection of E. coli O157:H7 — the strain that causes the majority of serious, E. coli-related illness — within eight hours.

Foodborne outbreaks will continue to occur, but with faster, more efficient diagnostics, we can intervene more effectively, better manage these outbreaks and prevent the spread of foodborne illness. With the progress of tools like PulseNet and advances in rapid diagnostic technology, our food is safer now than it was 20 years ago. And I firmly believe that 20 years from now, we will be able to say the same thing.

J. Stan Bailey is currently the Director of Scientific Affairs for bioMérieux Industry. Before joining bioMérieux, Inc., he worked as a research scientist for the U.S. Department of Agriculture from 1973 to 2007, and in 2002, was named Outstanding Senior Research Scientist. He can be reached at stan.bailey@biomerieux.com.