Courtesy of Zeresenay Alemseged, Dikika Research ProjectThe fossilized shoulder blades of a 3.3 million-year-old hominin, Australopithecus afarensis, suggest that it spent a lot of time climbing trees, despite being able to walk upright. The new evidence, published today (October 25) in Science, adds fuel to a 30-year-old debate over whether these direct ancestors of Homo species abandoned their forest canopy retreats to spend their lives on the ground—and the heated discussion continues.

Courtesy of Zeresenay Alemseged, Dikika Research ProjectThe fossilized shoulder blades of a 3.3 million-year-old hominin, Australopithecus afarensis, suggest that it spent a lot of time climbing trees, despite being able to walk upright. The new evidence, published today (October 25) in Science, adds fuel to a 30-year-old debate over whether these direct ancestors of Homo species abandoned their forest canopy retreats to spend their lives on the ground—and the heated discussion continues.

“This contribution adds usefully to the growing evidence that early hominins remained partially arboreal or at least retained 'arboreal adaptations' for a long time,” primate evolutionary biologist Robin Huw Crompton of the University of Liverpool wrote in an email to The Scientist.

Australopithecus afarensis’s anatomy falls halfway between that of an ape and that of a human, and the species “is a testament to the progressive, gradual process of evolution,” said senior author Zeresenay Alemseged,...

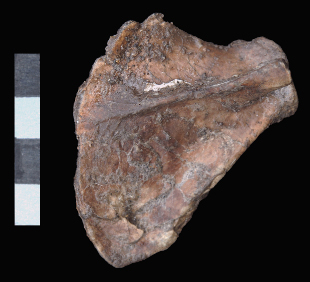

The new data come from a 3.3 million-year-old skeleton of a 3-year old girl, known as “Selam,” which Alemseged discovered in 2000 in Dikika, Ethiopia. After spending 11 years painstakingly extracting the skeleton from sandstone, Alemseged and his collaborator, anatomist David Green of Midwestern University, focused on the shoulder blades, or scapulae.

Courtesy of Zeresenay Alemseged, Dikika Research Project“Across mammals, and particularly across primates, the scapula seems to be a pretty good indicator of loco-motor style,” said Green, lead author on the study. In general, “you can look at a scapula of an individual and be pretty confident that this was a suspensory climber, or a [ground-dwelling] quadruped,” for example, he added.

Courtesy of Zeresenay Alemseged, Dikika Research Project“Across mammals, and particularly across primates, the scapula seems to be a pretty good indicator of loco-motor style,” said Green, lead author on the study. In general, “you can look at a scapula of an individual and be pretty confident that this was a suspensory climber, or a [ground-dwelling] quadruped,” for example, he added.

Alemseged and Green measured both of Selam’s fragile, paper-thin scapula, then compared their structure to that of two adult A. afarensis specimens, other early hominin species, and chimpanzees, gorillas, orangutans, and humans. The researchers determined that the overall shape and joint angle of Selam’s scapulae looked more ape-like than human-like. They also compared adults and juveniles of each species and found that A. afarensis’s scapulae growth more closely resembled that of apes.

The new study showed that these hominins “were bipedal creatures that also practiced arboreal locomotion or arboreal lifestyle—maybe for nesting, or evading predators, maybe for provisioning,” Alemseged said. “[It] is not a big surprise because they lived in a forest environment.”

Human evolutionary biologist and anatomy expert Brian G. Richmond of George Washington University, who was not involved in the study, thinks the data are convincing. “Bones are responsive to how you use them while you grow up,” he explained. “For example, if you play tennis intensively as a young kid growing up, the racket bearing arm actually grows much more robust and the bone itself can be some 30 percent bigger and stronger than the other arm. And [Selam] is showing us that the growth of the shoulder in Australopithecus matches what you’d expect if Australopithecus was still climbing in trees a lot as part of their regular activities.”

“And, if you think about it, it makes sense,” human evolutionary biologist, Daniel Lieberman, of Harvard University, wrote in an email to The Scientist, “climbing trees is very useful, and why would walking upright make you bad at climbing?”

But others question the authors’ interpretation of the data, arguing that it’s difficult—if not impossible—to merely look at a bone and determine if it’s shape and development is due to the animal’s behavior or just genetics.

“Primitive traits may be retained either actively by selection, or because there was no selective reason to change them,” explained Carol V. Ward, an anthropologist and anatomical scientist at the University of Missouri, who was not involved in the study. The differences between the scapulae of A. afarensis and modern humans “might reflect more climbing,” she wrote in a statement, or, “it may be that humans differ from apes in ways that reflect use of the forelimb for other, manipulatory functions, such as tool use or throwing.”

Richmond expects that the controversy on the topic is not over. “I think until they find a whole tree that’s fallen down with hominins in it, this is going to be a hard debate to totally settle.” But, he stressed, the discussion has now become more nuanced. “No one would argue that they can’t climb; it’s just a question as to the extent.”

D.J. Green, Z. Alemseged, “Australopithecus afarensis scapular ontogeny, function, and the role of climbing in human evolution," Science, doi:10.1126/science.1227123, 2012.

Interested in reading more?