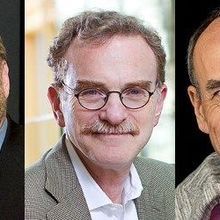

James Rothman, Randy Schekman, Thomas Südhof (left to right) NOBELPRIZE.ORG, H GOREN © HHMI, FISCH Randy Schekman returned from Germany last night only to be woken up after a few hours of sleep by his wife yelling, “This is it!” after she heard the phone ring. “I snapped to attention,” Schekman told The Scientist. “My heart started to race.” The voice on the other end told him he had won the Nobel Prize. Schekman, a professor at the University of California, Berkeley, and two others—James Rothman of Yale University and Thomas Südhof of Stanford University—share the Nobel in Physiology or Medicine this year for their discoveries in the fundamental mechanisms of trafficking cellular cargo.

James Rothman, Randy Schekman, Thomas Südhof (left to right) NOBELPRIZE.ORG, H GOREN © HHMI, FISCH Randy Schekman returned from Germany last night only to be woken up after a few hours of sleep by his wife yelling, “This is it!” after she heard the phone ring. “I snapped to attention,” Schekman told The Scientist. “My heart started to race.” The voice on the other end told him he had won the Nobel Prize. Schekman, a professor at the University of California, Berkeley, and two others—James Rothman of Yale University and Thomas Südhof of Stanford University—share the Nobel in Physiology or Medicine this year for their discoveries in the fundamental mechanisms of trafficking cellular cargo.

Each has made major contributions to understanding the organization of how vesicle contents are discharged at the cell membrane. And each came to similar answers from different angles. Schekman focused on yeast genetics, while...

At 4:00 AM, EDT, this morning, Schekman called his best friend, Bill Wickner at Dartmouth College, to tell him the good news. Wickner told The Scientist he was not surprised to hear that Schekman and the others had won. “It's been clear” they would, said Wickner, who has had decades-long relationships with each of the winners. He even introduced Schekman to his wife.

“They're three very different people. Each is very intelligent, very purposeful and driven,” Wickner said. “I love each one of them. They're fun, they love to talk shop. They're good listeners as well as speakers.”

Südhof is well known for his role in discovering the neuronal SNARE proteins, involved in fusing vesicles to the membrane, and also for discovering the proteins involved in linking electrical activity in neurons to calcium flux and the triggering of SNAREs in vesicle fusion. Ege Kavalali, a University of Texas Southwestern neuroscientist, collaborated with Südhof on some of the research into synaptic cell adhesion. “[Südhof’s] most important contribution was that he actually found the mechanism for how calcium stimulation triggers neurotransmitter release,” he told The Scientist. “I’m exceptionally ecstatic and incredibly happy for him. It’s incredibly well deserved.”

Rothman developed an assay to measure membrane fusion. It “was a key to developing the biochemistry and biochemical analysis of in vitro trafficking,” said Wickner. Claudio Giraudo of the Children's Hospital of Pennsylvania, who worked in Rothman's lab for eight years, said that Rothman “revolutionized” the way people could ask questions by developing his in vitro fusion assays, “an approach nobody tried to do,” Giraudo added. “He's a very smart person I admire a lot.”

Some of the proteins Rothman identified turned out to be the same ones Schekman identified genetically using yeast. Jonas la Cour, a postdoc at the University of Copenhagen, recently worked in Schekman's lab as a visiting researcher. Schekman, who he described as “fun and accessible,” was welcoming and had invited la Cour to his home.

Schekman said the Nobel Prize will be a distraction for a while, but his focus will continue to be on his laboratory and as editor-in-chief of the new online publication, eLife.

Interested in reading more?