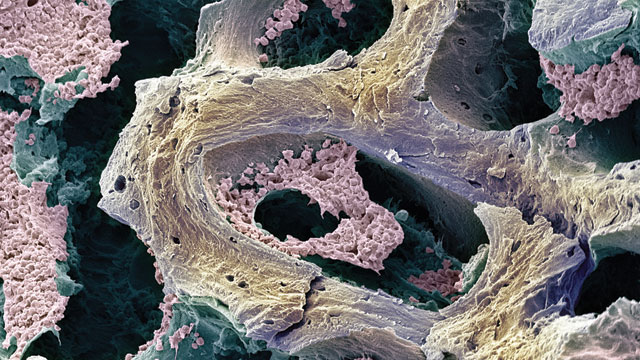

Bone marrow, with differentiating leukocytes in pinkSTEVE GSCHMEISSNER / PHOTO RESEARCHERS, INC.

Bone marrow, with differentiating leukocytes in pinkSTEVE GSCHMEISSNER / PHOTO RESEARCHERS, INC.

A

cute myeloid leukemia (AML) is a cancer of the blood-cell producing bone marrow with several subtypes, and is usually fatal within months, or even weeks, if left untreated. It is now becoming clear, however, that dysregulation of microRNAs (miRs) is not simply a side effect of the cancer; rather, it could play a mechanistic role in the development of leukemia.

Correlation or causation?

AML subtypes are classified according to the kind of cells in which the cancer originated, as well as the presence of several characteristic chromosomal alterations. Fusion proteins, for example, are the product of some of these chromosomal translocations and can be oncogenic. Recent studies have suggested that AML subtypes might also be characterized by their miR expression patterns. MicroRNAs are short (18 to 22 nucleotides), noncoding RNAs that regulate gene expression by base-pairing...

What has confounded researchers is that miR profiles change significantly during normal blood cell differentiation—a process that is arrested or actively reversed in many cancer cells. MiR expression is also deregulated in many types of cancers, including leukemias. Therefore, it has been unclear whether miR expression is an outcome of the disordered cell or the cause of the disorder.

Interestingly, some of these associations between miRs and leukemic subgroups could prove useful clinically, as miR expression signatures appear to correlate with AML survival rates.1 Because prognosis and treatment vary according to subtype, and subtypes have distinct gene expression profiles, the relationship between the expression of a specific miR (or a group of miRs) and AML subtype could have implications for prognosis and treatment of the disease.

But even prognostic associations come short of proving that the miRs are causing the malignant changes. Since miR activity spikes during normal blood-cell differentiation, it is possible that miR expression changes as a result of the cancer cell’s specific differentiation stage during oncogenesis and may not have a causal role in the leukemic process. While this may indeed be true of some miRs, evidence is accumulating that other individual miRs affect the development of AML.

MicroRNA action

The first evidence for a causal relationship came from Jianjun Chen and Janet Rowley’s lab at the University of Chicago. The group noticed that two specific miRs—miR-126 and miR-126*—were upregulated in the AML subgroups carrying chromosomal alterations t(8:21) and inv(16). When they forced the expression of miR-126 in other AML subtype cells they saw inhibition of apoptosis, thus increasing cancer-cell viability.2 Additionally, this miR enhanced the potential of mouse bone marrow progenitor cells to undergo immortalization. They showed that one of the genes that miR-126 silences is a known tumor suppressor. In AML, the increased expression of miR-126/126* appears to be due to an epigenetic effect, more promising for therapy options than chromosomal rearrangements.

Another miR—miR-29b—was also implicated in the AML subgroups with t(8:21) and inv(16) alterations by Guido Marcucci and colleagues at Ohio State University. They found that the decreased expression of miR-29b indirectly causes increased expression of KIT, a tyrosine kinase overexpressed in several human cancers.3 This finding is of particular interest because augmented KIT expression is associated with decreased survival in patients in this subgroup, which is otherwise associated with a good prognosis.

Potential causative roles for miRs have also been described in AMLs with fusion genes involving the mixed lineage leukemia (MLL) gene and are associated with a poor prognosis, requiring intensive therapy. Nancy Zeleznik-Le and colleagues at Loyola University Medical Center4 showed that the MLL-AF9 fusion gene caused overexpression of miR-196b. Bone marrow progenitor cells transfected to produce an MLL fusion protein displayed increased proliferation, which could be reduced by inhibiting the expression of miR-196b. Furthermore, forced expression of this microRNA caused increased survival and proliferative capacity in bone marrow progenitor cells.

It appears that miR-196b isn’t the only microRNA at play in the MLL subtype. The miR-17-92 cluster of miRs functions in a similar fashion—their overexpression increases proliferation and decreases apoptosis.5 But what’s more interesting is that the MLL fusion proteins bind the promoter region of the miR17-92 cluster more strongly than the wild type MLL, resulting in an increased expression of these miRs. This indicates that these miRs not only play a functional role in MLL leukemia, but are also the direct targets of the fusion genes.

Deregulated expression of miRs can be an important step in leukemogenesis, and expression of miRs can be affected by a number of different oncogenic mechanisms. As an individual miR is likely to affect the expression of several different genes, understanding how to control irregular miR expression raises the potential for therapeutic strategies targeting multiple leukemogenic processes.

Associate Faculty Member Katherine Hyde and Faculty Member Paul Liu are at the NHGRI/NIH, Bethesda.

This article is adapted from an F1000 Biology Report (DOI: 10.3410/B2-82), a publication of the Faculty of 1000. F1000 consists of more than 5,000 experts in biology and medicine who select and evaluate the most important published papers in their respective specialties. The ‘Editor’s Choice’ selections describe articles recently evaluated in F1000.

References

- G. Marcucci et al., “MicroRNA expression in cytogenetically normal acute myeloid leukemia,” N Engl J Med, 358:1919-28, 2008. Free F1000 Evaluation

- Z. Li et al., “Distinct microRNA expression profiles in acute myeloid leukemia with common translocations,” PNAS, 105:15535-40, 2008.

- S. Liu et al., “Sp1/NFκB/HDAC/miR-29b regulatory network in KIT-driven myeloid leukemia,” Cancer Cell, 17:333-47, 2010.

- R. Popovic et al., “Regulation of mir-196b by MLL and its overexpression by MLL fusions contributes to immortalization,” Blood, 113:3314-22, 2009.

- S. Mi et al., “Aberrant overexpression and function of the miR-17-92 cluster in MLL-rearranged acute leukemia,” PNAS, 107:3710-15, 2010.