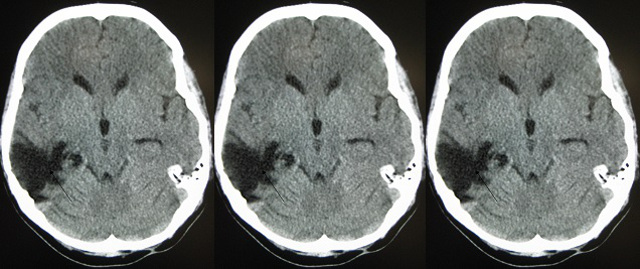

WIKIMEDIA, JAMES HEILMANWhen doctors are testing new drugs or treatments for diseases, randomized controlled clinical trials are considered the gold standard. But in my field of traumatic brain injury (TBI), this gold standard approach is not working. Over the last three decades, dozens of Phase 3 clinical trials evaluating TBI treatments have failed to provide solid evidence of patient benefit.

WIKIMEDIA, JAMES HEILMANWhen doctors are testing new drugs or treatments for diseases, randomized controlled clinical trials are considered the gold standard. But in my field of traumatic brain injury (TBI), this gold standard approach is not working. Over the last three decades, dozens of Phase 3 clinical trials evaluating TBI treatments have failed to provide solid evidence of patient benefit.

When a therapy reaches Phase 3 clinical trials, it has already been tested in animals and in early-stage human studies. Each and every TBI drug that has reached late-stage clinical trials has failed. This 100 percent failure rate represents a huge human and economic cost. Why is this happening?

It is possible that the drugs tested just don’t work. Alternatively, some treatments may have been helping patients, but they were tested in a format where the benefit was not discernible above statistical noise.

I believe clinical trials for TBI...

My research on progesterone grew out of the observation that female animals and women tend to better recover from TBI than their male counterparts—a phenomenon first reported in the 1970s. In animal studies, my team and several others around the world found that progesterone can reduce the metabolic cascade of damage that accompanies TBI and other forms of brain injury.

In contrast, two large Phase 3 clinical trials of progesterone for TBI—one sponsored by the National Institutes of Health (NIH); the other, privately funded—were stopped in 2014 because they did not show a clear benefit to patients. Looking back on these two studies, I see several factors that may have interfered with the ability to detect success of this treatment, including:

- That TBI patients are a heterogeneous group. The location and extent of injury varies, as does the time it takes for a patient to reach a hospital. On top of that, patients’ underlying resilience and capacity for recovery may be affected by age, sex, and pre-existing conditions. Enrolling everyone with a “TBI” regardless of locus and cause of injury can substantially add to variability of outcome.

- Insufficient recovery metrics: tools like the Glasgow Coma Scale are blunt instruments for measuring the complexity of brain injury and recovery, and patients are not always the best judges of the extent and quality of their conditions.

- Insufficient dose optimization: a retrospective analysis taking into account the physiological differences between rodents and humans, has suggested that patients received doses of progesterone that were substantially higher then the optimal doses derived from the animal studies.

The commendable goals of speed, including as many patients as possible and reducing costs undoubtedly drove study design choices. Still, doing more preliminary research first could have saved time and money later on. Future clinical trials ought to:

- Refine patient selection criteria. The field of stroke has a record of clinical success that has been almost as dismal as that of TBI. An exception came with recent studies showing the benefit of endovascular clot-removal devices, which were only successful after better patient selection criteria were adopted. For TBI, this may include stratification by age, sex, or type of injury.

- Adopt adaptive designs, which allow for changes in group assignments as the trial progresses, rather than having initial assignments locked in. In 2010, the Food and Drug Administration issued a draft guidance on adaptive design studies. These trial designs are more prevalent in oncology, where outcomes can be measured unambiguously (through the disappearance of cancer cells or patient survival). Encouragingly, Alzheimer’s disease researchers have begun to embrace adaptive trial designs.

- Include multiple quantitative outcome measures that are more likely to reveal the extent and duration of recovery. Fortunately, more fine-grained outcome measures are available, such as those assembled by the NIH Toolbox for the assessment of neurological and behavioral function. Collaborators on the Department of Defense-funded TBI Endpoints Development Award are working toward this goal.

- Require more optimization of dose and route of administration, with a firmer understanding of drug mechanism and metabolic characteristics.

Although I believe that the current research-based evidence points to another try for progesterone, my primary goal is to help find a safe and effective treatment for TBI, whatever the agent turns out to be. Taking into account preclinical experiments with a variety of different drugs whose mechanisms are known, the 100 percent failure rate for TBI clinical trials strongly suggests that the problem may be more with study design.

As researchers continue to move treatments for complex neurological disorders through clinical trials, it is imperative that we learn from past mistakes.

Donald Stein is an Asa G. Candler and Distinguished Professor in Emergency Medicine at Emory University School of Medicine in Atlanta. He continues to conduct research on the neuroprotective properties of neurosteroids and, along with Emory, holds patents on progesterone for use in CNS injuries but receives no licensing fees or royalties.

Interested in reading more?