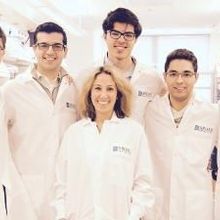

Left to right: Dustin Shahab Griesemer, Shervin Tabrizi, Pardis Sabeti, Siavash Zamirpour, Kian Sani, Mahan NekouIMAGE COURTESY OF PARDIS SABETIBefore Time named her one of 2014’s most influential people for her work on the genetics of Ebola in West Africa, before she won a Howard Hughes Medical Institute Investigator award, before she embarked on a scientific career, Harvard University’s Pardis Sabeti was 2-and-a-half-year-old who was bustled out of Iran with her family, mere months before the country’s Shah was overthrown in 1979.

Left to right: Dustin Shahab Griesemer, Shervin Tabrizi, Pardis Sabeti, Siavash Zamirpour, Kian Sani, Mahan NekouIMAGE COURTESY OF PARDIS SABETIBefore Time named her one of 2014’s most influential people for her work on the genetics of Ebola in West Africa, before she won a Howard Hughes Medical Institute Investigator award, before she embarked on a scientific career, Harvard University’s Pardis Sabeti was 2-and-a-half-year-old who was bustled out of Iran with her family, mere months before the country’s Shah was overthrown in 1979.

“My dad was basically a high-ranking intelligence officer,” Sabeti told The Scientist. “So he was one of the folks that would be the most targeted by the new regime, which is why he made sure that we got out right away.”

Sabeti, along with her mother, sister, cousins, grandparents, and other relatives first landed in Hawaii. “I just remember being in these houses with like...

For her first 10 years, Sabeti lived a peripatetic childhood, moving from Hawaii to Florida to New Jersey and then back to Florida. “We were always super patriotic to America from the get-go. We felt immediately pretty welcome,” Sabeti said. “People were really nice to us everywhere we went. We were immediately just incredibly grateful to the country.”

Sabeti’s home life primed her to become a leading thinker in her field. Her mom set up a yearly summer school for Sabeti, her older sister, and a cousin who would stay with them. “She decided that my sister was going to be the teacher of summer school and that my sister would teach my cousin and I class every day,” Sabeti recalled. “So she got a chalkboard, she got a bunch of really crappy textbooks from some garage sale of some sort, and basically set up.”

Officially becoming a US citizen when she turned 18, Sabeti enrolled at MIT to follow her passion for mathematics and science, thinking a medical degree was her ultimate goal. But then she met geneticist Eric Lander, founding director of the Broad Institute. “I was always interested in nature,” Sabeti said. “Eric Lander taught me I could have an impact on health through science and particularly mathematics. And genetics is really nature as seen through mathematical information. That really hit every button for me.”

Since joining the Harvard faculty, Sabeti has established a more than 30-person lab, focused primarily on the genomics of infectious diseases. Early in her career, she created several algorithms to mine the human genome for indicators of adaptive variation, such as infectious disease-resistance. Her group made waves when they traveled to West Africa during the height of the Ebola epidemic there, releasing genomic sequences of the virus to the public as they were published. “That was just something different from what people did. We did that, and we moved really quickly, and we still got the big paper, and we still got the things that you might want to get,” she said. “It really showed people that you don’t have to hide or be a jerk or try to push other people out. You can be successful by being open and by helping.”

See “Ebola Outbreak Strains Sequenced”

But Sabeti considers her work as a mentor even more important than her scientific achievements. “My proudest accomplishment is training a lot of scientists who have gone on to have their own careers, and just seeing that whole trajectory,” she said. “That’s the amazing thing about being a scientist—that you’re not just doing one thing. There’s a real component of community a lot of people don’t understand.”

And her lab includes many immigrants, some of whom hail from her native Iran but also from China, Russia, and other countries. “At one point, we were like, ‘Are we the ‘axis of evil?’ What’s happening here?’” she joked.

Sabeti said that the Trump administration’s treatment of immigrants and refugees, especially those from Iran, Iraq, Syria, Sudan, Yemen, Libya, and Somalia—the countries included on the executive order on immigration signed by the new president—is a worrying development. “All of my foreign-born students, we have to go to Africa and things often. They’re all holding off on any of them going, because we wouldn’t want them to not be able to get back into the country,” she said. “This is the worry, that this could be the first of many different kinds of restrictions. There’s a lot of anxiety about what’s going to come in the next couple of years, for sure.”

Although she has been recovering for several months from a near-fatal accident she sustained in 2015, Sabeti said she has thought a lot about going into politics herself. “It’s always been something of interest to me,” she said. “You don’t just want to be talking from the sidelines always. I do think it would be helpful if there were a lot more people with science backgrounds in politics.”

Sabeti has participated in protests for women and immigrants since President Trump took office, but she said that, right now, she would really like to show people that most researchers from Iran—and anywhere else—come to the U.S. to help people. “They’re just individuals wanting to make a positive impact in the world, and they’re trying to find a place to be able to do it. We really just need to support people to do that work,” she said. “Often my Persian students are so grateful to have this opportunity to do good. It’s just really tragic that we’re not being incredibly grateful and supportive of people who want to make a difference.”

Interested in reading more?