GOING PUBLIC: Gajus Worthington, founder and CEO of Fluidigm, and the rest of the California-based biotech team in Times Square on February, 10, 2011, the day the company went public, raising $75 million. NASDAQ STOCK EXCHANGE

GOING PUBLIC: Gajus Worthington, founder and CEO of Fluidigm, and the rest of the California-based biotech team in Times Square on February, 10, 2011, the day the company went public, raising $75 million. NASDAQ STOCK EXCHANGE

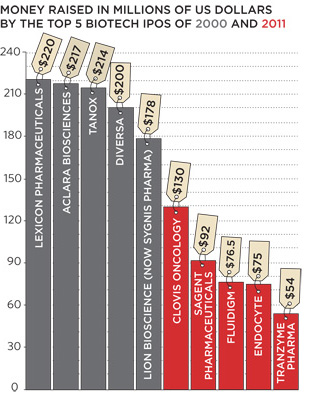

In 2000, Wall Street fell in love with biotechnology. Biotech stocks flew off the shelves as investors clamored to get cozy with companies working on tantalizing new concepts like “genomics” and “gene-based therapies.” In total that year, US biotechs completed 63 initial public offerings (IPOs), raising $5.4 billion in funding.

But that love affair has long since soured. Gajus Worthington remembers the falling-out vividly. “It was a nightmare,” recalls Worthington, CEO of Fluidigm, a California-based biotech tools company. Fluidigm had plans to “go public”—issue shares of stock in the open market for the first time—in late September 2008. But on Sunday, September 14, mega-investment banks Merrill Lynch and Lehman Brothers collapsed and the stock...

If you’re a fund manager,

and you bought all the 17 [biotech] IPOs in 2011, you’d be about 27 percent underwater today.

-G. Steven Burrill, Burrill & Company

In 2008, 19 biotech companies withdrew their IPO registrations. Only one followed through, raising a meager $6 million when it made its public debut. In the last 4 years, the annual number of biotech IPOs has slowly climbed, but investors remain tentative. Today, biotechs can still complete successful IPOs—raising money to fund drug trials and product development—but public offerings overwhelmingly don’t make as much money as companies expect. What’s more, investors have higher standards than they used to.

In 2000, for example, a biotech could pull off a brilliant IPO with just a whiff of preclinical data. Today, the only companies that perform well at their IPOs are those that have late-stage drug candidates, products already on the market with a demonstrated revenue stream, or trusted management teams. “The color of companies going public today is dramatically different than it was pre-financial crisis,” says G. Steven Burrill, CEO of Burrill & Company, a life sciences financial services firm. “There is less interest in owning risk, so the companies that do go public today are substantially risk-mitigated companies.”

This doesn’t make the market “closed” per se, as a company can go public at any time, he adds. “It’s just a poor time to take your [biotech] company public because there is virtually no appetite.”

“It’s tough to get an IPO done,” agrees Thomas Coll, head of business and technology at Cooley LLP, an international law firm, who has overseen numerous biotech IPOs. “The companies that have gotten it done in recent years are, for lack of a better term, unconventional.”

Winners and losers

After a poor showing in 2008, the following year wasn’t much better for biotech IPOs. “In 2009, you had as much chance of making it to the moon and back as you did flying a new life sciences offering on Wall Street,” wrote the editors at FierceBiotech, an industry publication, in a 2011 review of the field.

Then, in 2010, 13 companies mustered their courage and financial records to make the public leap. The first and one of the most successful biotech IPOs of the year was Ironwood Pharmaceuticals, which raked in $188 million—more than any other biotech since 2002—when it went public on February 3, 2010.

Despite the ailing stock market, the firm was confident heading into the IPO because it had already “sort of cheated,” says Ironwood CEO Peter Hecht. Over the 5 preceding years, the company had received several large investments from firms that traditionally funded only public companies, allowing Ironwood to stay private for longer than usual, allowing the biotech to go public with a product, for the treatment of irritable bowel syndrome, that had already completed phase III trials. Plus, those same investors were then poised and ready to purchase more of the company when the IPO opened. Ironwood’s so-called “insider” investors contributed $74 million, almost 40 percent, of their total IPO, according to analysts. “By the time we were going public, it was sort of a done deal,” says Hecht.

“If you look at the IPOs in the biotech space over the last couple of years, they’ve all had significant insider participation in order to make it possible,” says Gordon Link, chief financial officer (CFO) of NewLink Genetics, which went public in 2011. Bruce Booth, a partner at Atlas Venture, a life sciences venture capital firm, describes such insider help as biotech’s “dirty little secret.” “You need insiders who can do this or don’t even bother trying to go public,” he advised on his biotech blog in May 2011.

A month after Ironwood completed its IPO, Aveo Pharmaceuticals took their shot. After meeting with over 30 potential investors at the end of 2009, “we decided to pull the trigger and go public,” says Tuan Ha-Ngoc, president and CEO of Aveo. The financial markets were still in turmoil, but the company was gearing up for a costly phase III trial for its lead candidate—an oral, once-daily drug for kidney cancer—and needed the influx of capital.

In March 2010, the company completed its IPO at $9 per share, lower than the $13–$15 price range they had predicted, and raised $81 million. Eight months later, the company raised an additional $61 million through the sale of stock to several private investors, and in June 2011, topped it off with an additional $104 million from a second public offering—a total of $246 million from the sale of stock.

“The key is not to listen [for] the bankers to say if [the] market is open or not,” says Ha-Ngoc. “Go out and talk to the people who will write the checks and buy the shares. They will tell you.”

But 2010 wasn’t all sunshine and roses. Tengion, a biotech in phase I clinical trials for a regenerative medicine technology, went public in April that year with shares going for significantly below its expected $8 to $10 range, raising only $30 million. In the same month, French immunotherapy company Neovacs, braving the first biotech IPO in France in 2 years, raised a measly $13.5 million—roughly half the amount the company initially sought.

Last year was similarly mixed in terms of IPO successes. Fluidigm, which had been keeping an eye on the market since its failed attempt to go public when the markets crashed in 2008, decided to give it another go. This time, the company, which sells microfluidics-based chips and other lab instrumentation, whipped the offering together in just 3 months, half the time it had taken in 2008. “We kept our engines hot,” says CEO Worthington. “We figured there was a chance the market would change, and when it did, we’d be ready to go.” The company raised $75 million when it debuted in February 2011.

In November, Clovis Oncology, a biopharmaceutical company founded in 2009, completed the largest biotech IPO of the year. With three anticancer drugs in its pipeline, two of which were in midstage clinical trials, the company raked in $130 million through the sale of 10 million $13 shares.

In addition to having midstage drug candidates, the company’s successful IPO can be attributed to its well-known management team—four former execs of Pharmion, a cancer-focused biotech that sold for $2.9 billion in 2007. “Rightly or wrongly, that’s important to investors,” says Erle Mast, Clovis’s CFO.

Other companies were less successful. NewLink Genetics, an Iowa-based cancer vaccine developer, also made its public debut in November, but raised only a modest $43 million, selling 6.2 million shares for $7 each—significantly below the $10 to $12 at which the company had hoped to sell. “We went out with what we thought was a fair and supportable price, and the institutions didn’t agree with us,” says CFO Link. “We knew it would be difficult—it’s a buyers’ market.”

Squeezing through the window

So how have the newly public biotechs fared on the open market? In a nutshell, not well. Though a few announced strong positive clinical endpoints, to the joy of their shareholders—including Aveo and Ironwood, whose stock prices have increased by 54 percent and 30 percent, respectively—others slid precariously below their offer price. Following research setbacks, Tengion is now trading for pennies at 86 percent below its IPO price. Pacific Biosciences, which in September laid off 28 percent of its workforce, saw its stock price dwindle from the original offering of $16 per share to as low as $3 per share, an 81 percent drop.

“If you’re a fund manager, and you bought all the 17 [biotech] IPOs in 2011, you’d be about 27 percent underwater today,” says Burrill. “There’s very little incentive for investors to participate.”

IPOX Schuster, a fund that specializes in investing in newly public companies, will occasionally include biotechs in investor portfolios, but only on a limited basis, says the company’s founder and director, Josef Schuster. “If you have $100,000 in your portfolio, these [companies] should probably not become more than 3 or 4 percent of that,” he says.

And this year is “not going to be any different,” predicts Schuster. “Investor interest remains muted.”

Still, a few companies are taking their chances. On January 27, Cambridge, Massachusetts-based Verastem, a preclinical biopharmaceutical company, bucked the trend by raising a surprising $55 million. That coup may be due to the company’s high-profile cast of renowned founders from MIT’s Whitehead Institute and experienced CEO Christoph Westphal, who developed and sold Sirtris Pharmaceuticals to GlaxoSmithKline for $720 million in 2008. A few weeks later, North Carolina-based Cempra Pharmaceuticals, which has two novel antibiotics that have successfully completed phase II trials, completed a $48 million IPO, raising considerably less than the $90 million they had expected.

Other potential 2012 IPOs include Rib-X Pharmaceuticals, also an antibiotic developer, which filed its IPO registration notice with the US Securities and Exchange Commission in November 2011, disclosing plans to raise $80 million to help launch a phase III study. And Supernus Pharmaceuticals, which filed in December, hopes to raise $100 million through a 2012 IPO. The firm’s lead product, SPN-538 for epilepsy, received FDA approval in November 2011.

“There are many, many biotech companies that are poised and ready to file,” says Coll. But with a volatile market and the fact that it is an election year, there isn’t likely to be a dramatic change in the number of biotechs going public. “It’s tough out there,” he says. “Keep your eye on a possible IPO window, but also look at other funding mechanisms at the same time.”

And if that window appears, don’t miss it, adds Worthington. “If you are ready to go, go as fast as humanly possible. The market can change in a day.”

Correction: This story has been updated from its original version to correctly state that Clovis Oncology raised $130 million in their 2011 IPO through the sale of 10 million $13 shares. The Scientist regrets the error.

Interested in reading more?