The career outlook for life scientists hit a rocky patch at the start of the 21st century. Although the 1990s brought a boom in jobs, the failure of genomics companies to quickly produce marketable products dampened venture capitalists' enthusiasm for early-stage biotechnology, and the market slowed. The US economy in general began to decline, and in 2002, unemployment for scientists reached 3.9%, a 20-year high.

However, even during the darkest times, unemployment among scientists was always lower than among workers in other industries (see figure, United States Unemployment Rate by Occupation, 1983-2002 below). This suggests that it is still easier for scientists to find jobs than it is for the average US worker. And, some signs indicate that the life sciences industry is picking up: Venture capitalists are still willing to invest in biotechnology, and some fields, such as bioinformatics, need workers. Indeed, the government predicts that the number of...

SIGNS OF LIFE

According to the US Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS), 213,994 people were working as life scientists in 2002, and by 2012, that number should increase to 252,987, a jump of 18%. Moreover, the BLS predicts that from 2000 to 2010, employment among scientists will increase three times faster than it will in other occupations.

Not all sectors of the life sciences will benefit equally from this growth. "There's definitely going to be pockets of strengths and weaknesses," says Henry Kasper, an economist at BLS in Washington, DC. For instance, the BLS predicts that scientific research and development services will increase by 19%, while pharmaceutical and medicine manufacturing may rise a whopping 36%. Government jobs are expected to climb by a relatively meager 13%.

Other data suggest that life scientists should generally feel secure about their employment. A poll of 1,678 life science professionals in January 2004 by the Science Advisory Board, an Arlington, Va.-based organization that conducts surveys of medical and life science professionals for companies that sell them products and services, showed that only 3% worried about tenure, and even less were concerned about the threat of work-place mergers or acquisitions, which often involve layoffs. Moreover, a survey of 101 senior executives in healthcare companies by the communications agency B360 in California showed that most described the outlook for 2004 as above average, and more than 80% said they planned to add jobs.

MORE OF THE SAME LIKELY IN ACADEMIA

Projected Increase in Employment

The career landscape for academic life scientists has changed quite a bit over the past 20 years. In the mid-1970s, more than 80% of biomedical PhDs in academia were tenured faculty or on a tenure-track, and less than 10% were working as postdocs, according to the National Academy of Sciences. By the end of the 1990s, however, only around half of working PhDs in academia were tenured or on their way to becoming so, and the number of postdocs had risen to more than 18%.1

Simultaneously, the number of faculty not on a tenure-track increased more than 10-fold, a trend that continues today, says Jim Voytuk, senior project officer at the National Research Council in Washington, DC. Non-tenured faculty have the disadvantage of knowing that they could be laid off at any time, Voytuk notes, and that some, if not all, of their salary depends on research grants. If that money disappears, their jobs may, too, he says.

In terms of funding, BLS predicts that PhDs in the biological sciences will likely continue to compete with each other for the few research positions available. Although the National Institutes of Health recently had a slight budget increase, the number of new PhDs entering the field is outpacing the available funds. Currently, only one in three grant proposals for long-term research is approved. If current enrollments in advanced degree programs persist, so will these trends.

TIPS FOR A 2005 JOB SEARCH

If you're planning on looking for a job in 2005, you won't be alone: According to a poll of 1,678 life science professionals in January 2004 by the Science Advisory Board, almost one-fourth said they planned to look actively for another job. Less than one-fourth said they felt their current salary was fair, given their age, education, and experience.

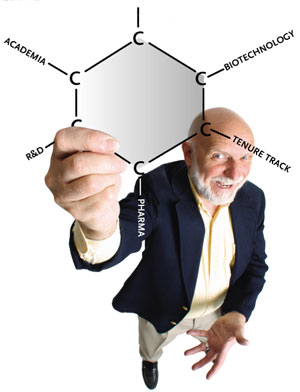

Clearly, even if life scientists are more likely to find a job than those in other industries, these jobs will not always be ideal, and scientists may need to be flexible if they want to stay employed, says Cynthia Robbins-Roth, founding partner of Bioventure Consultants in San Mateo, Calif., and author of

One big source of jobs is at one of the many biotech startups. Tamara Zemlo of the Science Advisory Board in Arlington, Va., says a new company "always" seems to be breaking ground in the Maryland area. Joining a startup can be risky, since poor business moves can waylay a good scientific idea. One way to increase the chances of success is to have a working knowledge of how communication, payroll, human resources, patent law, and other departments operate, since most early employees will need to pitch in as needed, she says.

Being flexible and business-wise will help protect life scientists from the ongoing job uncertainty that many, both new and more long-term, still face. "Don't be naïve," cautions Zemlo. "You need to develop some business savvy."

R&D: D WILL GROW MORE THAN R

By all accounts, life science companies in private industry are feeling the pressure to perform; they are focusing more resources on developing drugs with commercial promise, rather than on research. "I do believe biotech companies need to get to late stage as soon as possible," says Larry Stambaugh, chairman and CEO of Maxim Pharmaceuticals in San Diego. The company laid off 50% of its employees in 2004, leaving 56 employees remaining. Stambaugh says those cuts ran just as deep among Maxim's scientific workforce, but declined to say whether both research and development were equally hard-hit.

Current pricing pressures on drugs and threats on patent protection are partially responsible for a squeeze on hiring, says Asia Martin, spokesperson for Eli Lilly, which also made significant cuts in its scientific workforce in 2004, and has installed a hiring freeze that will last indefinitely. In addition, the recent withdrawal of Vioxx from the market may set off widespread fear among drug companies that they will need to spend more money investigating drugs before releasing them to consumers, says Buster Houchins of search firm Christian & Timbers in Columbia, Md. This and other pressures could encourage some companies to outsource their discovery and sales operations, creating fewer jobs at all levels. "I think we'll look back at 2004 and say pharma peaked," says Houchins, who helps place executives in life science companies.

As companies shift focus towards profits, people involved in bringing a drug to market, including preclinical or clinical testing, the FDA approval process, and marketing, are likely to have the best shot at employment in 2005. This includes scientists specializing in medicinal chemistry, toxicology, pharmacology, small-animal pharmacology, combinatorial chemistry, and bioinformatics. Other in-demand scientists are those with experience designing and running clinical trials, and working with the FDA on regulatory issues.

For instance, although Maxim lost half its workforce in 2004, CEO Stambaugh says the company will likely need more people to work on regulatory approval for Ceplene, a leukemia drug, and to run additional clinical studies. Scientists may also be needed to help with the commercial launching of Maxim products, Stambaugh predicts.

For life science executives, small companies will likely give preference to chief executives and officers who have already worked at startups and demonstrated that they can help a company successfully grow, says Nina Kjellson, a life sciences investor at InterWest Partners, a venture capital firm in Menlo Park, Calif.

The BLS also predicts that the future may look even brighter for non-PhDs than it does for holders of advanced degrees. People with bachelor's or master's degrees in biological science often qualify for science-related jobs in sales, marketing, or research management, and the government predicts those jobs will soon outpace the number of independent research posts.

EU OUTLOOK

United States Unemployment Rate,

In Europe, the job forecast for 2005 in all sectors looks very much like that in the United States, says Peter Nicholls, chair of the Personnel Advisory Committee at the BioIndustry Association, a UK-based bioscience trade organization. "We tend to follow the US," Nicholls notes. "So what happens in the States tends to happen [here] particularly in the UK, and in the whole of Europe soon after." In Europe over the next year, Nicholls predicts: Tenured, academic positions will likely be equally hard to come by; most available industry jobs will largely be in the area of developing and bringing a drug to market, rather than research; and venture capital will be sparsely available for biotechnology companies.

Even the United Kingdom's relatively progressive stance on stem cell research likely won't have much of an impact on jobs, notes Nicholls, who is also the director of Human Relations at the UK-based biotech company Celltech. Researchers still need to get a license from the government to do the work, Nicholls says, and most applications are refused.

However, basic research may see one bright spot on the EU horizon: Many of the former Eastern bloc countries such as Poland are building up a biopharmaceutical industry and "starting from scratch," meaning they will need scientists who have experience with research, rather than development, Nicholls notes. "They're not likely to have projects that are ready to go into development."

POCKETS OF WEAKNESS IN PRIVATE INDUSTRY

"Research is a luxury, simple as that," says Bruce Seligmann, president, CEO, and chairman of High-Throughput Genomics, an Arizona-based company that creates drug discovery tools. "And when times get tough, research gets a stranglehold around it," he adds. An ongoing emphasis on drug development means that many life science organizations may shift their focus away from discovery.

For small companies with small budgets, that may mean letting go of their researchers once a drug enters the development phase, says Thomas Laundon, chief operating officer at Synthematix, a chemical informatics company based in Research Triangle Park, NC. These companies "really have to put their eggs into the development basket," he says. This trend cannot continue indefinitely, since companies will always need more drugs to develop, but focus will not likely return to research in 2005, Laundon predicts.

Working as a researcher at a small startup may be precarious in 2005, but working for a pharmaceutical giant, which can always merge with another and eliminate thousands of jobs in one afternoon, is also no guarantee, says Seligmann. One advantage of being a scientist for a small company is that you can often predict when your job is in jeopardy, whereas when you are just one of thousands of employees, you can get "blindsided" by a round of layoffs, he says.

Now that venture capitalists are generally more cautious about the promise of biotechnology and more savvy about the time and expense required to bring a drug to market, any employee of a company that relies on funding from venture capitalists may be in for a bumpy ride in 2005, predicts Tamara Zemlo, director of scientific and medical communications at the Science Advisory Board. "If you decide to go into these high-risk ventures, it's just very difficult right now," she says.

An additional pressure life scientists might face in the future comes from outsourcing, now that countries such as China and the former Eastern bloc are working on strengthening their science and technological capabilities. India, for instance, is currently pumping up its bioinformatics industry, says Zemlo. This process will take a long time to complete, however, so scientists may not feel the burn of outsourcing in 2005, Zemlo notes. "I think it's a slow erosion," she says.

Clearly, some sectors of the life sciences may be in more trouble than others. But for people who've gotten accustomed to the economic climate of 2004, the next year will likely not bring any significant surprises and may instead bring, according to some, an improvement. "What I see in 2005 is a continuation of the behavior in 2004," says Laundon. "I personally am slightly more optimistic in 2005, but not greatly so."

Interested in reading more?