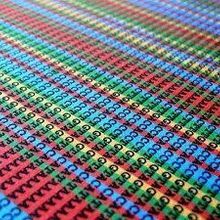

FLICKR, SHAURY NASHSubcontracted nucleic acid sequencing can be a source of extensive cross-sample contamination, warn the authors of a report published in BMC Biology last week (March 29). Approximately 80 percent of RNA samples collected from 180 different species as part of an evolutionary study became tainted with RNA sequences from other species, according to the authors. And most of this contamination occurred when the samples were sent to companies for sequencing.

FLICKR, SHAURY NASHSubcontracted nucleic acid sequencing can be a source of extensive cross-sample contamination, warn the authors of a report published in BMC Biology last week (March 29). Approximately 80 percent of RNA samples collected from 180 different species as part of an evolutionary study became tainted with RNA sequences from other species, according to the authors. And most of this contamination occurred when the samples were sent to companies for sequencing.

“The important take-home message is that all molecular biologists . . . need to consider contamination of research materials as a risk. None of us are immune to contamination, no matter how experienced we are or how good our technique. We need to be aware that our precious research materials may become contaminated, and think about ways to manage that risk,” Amanda Capes-Davis of CellBank Australia who was not involved with the research wrote in an email...

Study coauthor Marion Ballenghien was well aware of these risks. While working as a researcher in the lab of Nicolas Galtier at the Montpellier Institute of Evolutionary Sciences in France, Ballenghien was tasked with collecting and preparing hundreds of RNA samples from a variety of species as part of a comparative evolutionary genetics project called PopPhyl.

“We had so many species . . . in the lab, I was afraid that maybe I [would] contaminate something,” said Ballenghien, who now works at the Roscoff Marine Station—part of the French National Center for Scientific Research (CNRS). She did her best to prevent contamination, but also had a way to detect it should it happen. This was especially important, she explained, “because most of the samples were from nonmodel species,” meaning there was little transcriptome sequence data available for the sake of comparison.

After careful preparation, the PopPhyl team shipped its samples to a number of different sequencing centers, Ballenghien said. When the data came back, the team ran the contamination check—a search for sequences originating from species other than the one sampled.

Among other things, the researchers examined the sequences of any cytochrome oxidase 1 (cox1) transcripts present in the samples. Being a highly expressed mitochondrial protein present in all eukaryotic cells, cox1 is commonly used for determining the number and identity of different species in a given sample.

The team found that, of 446 RNA samples sent for sequencing (representing 116 distinct species), 353 exhibited cross-species contamination. And 205 of these samples were contaminated by at least two different species.

Because Ballenghien had been responsible for preparing most of the RNA samples, her initial thought was “Oh, crap.”

But because she had also been fastidious about documenting which samples were prepared when and by who, as well as when and where they were shipped, she and her colleagues were able to narrow down at which points contamination occurred.

Indeed, the team discovered that species that were shipped together had a much higher likelihood of contaminating each other than those that were prepared by the same person or during the same period (though these were also shown to influence contamination). Most of the apparent contamination events, Ballenghien said, likely occurred during sample processing at the sequencing facilities. “I thought the companies would have more checkpoints,” she said, “but I’m surprised that they don’t.”

Although a whopping 80 percent of the samples studied were contaminated, in most cases the damage was minimal and so would “not have an impact for many applications,” wrote Capes-Davis.

Regardless, “we need to be careful,” evolutionary biologist Stephen Smith of the University of Michigan wrote in an email to The Scientist. “We should expect authors to address the possibility of [contamination] when reporting results that might seem out of the ordinary.”

Can anything be done to prevent contamination? Ultimately, “it’s a never-ending problem because your dealing with molecules . . . they’re floating around and if they get from one container to another you don’t see it happen,” said Steven Salzberg of Johns Hopkins School of Medicine in Baltimore. “You can be very careful but . . . I don’t think there is any physical solution to keeping contaminating DNA out of every sample,” he added.

The outlook isn’t entirely gloomy. Awareness of the problem helps, said Salzberg. “The more people that write papers like this—that make others aware of contamination—the better,” he said. Furthermore, “as our database of known genomes grows, we [are increasingly able] to recognize more and more foreign organisms that might be in a sample.”

M. Ballenghien et al., “Patterns of cross-contamination in a multispecies population genomic project: detection, quantification, impact, and solutions,” BMC Biology, doi:10.1186/s12915-017-0366-6, 2017.

Interested in reading more?