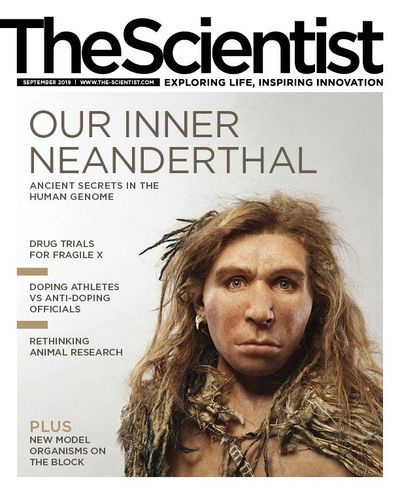

ABOVE: LAUREN DIAZ

When Clemson University master’s student Lauren Diaz set out to study the ecology of hellbender salamanders (Cryptobranchus alleganiensis) in the streams of western North Carolina, she anticipated some challenges. Although they can grow to two feet long, hellbenders—also known as snot otters, devil dogs, and Allegheny alligators—are difficult to find in the wild due to effective camouflage and their habit of hiding under rocks. And it’s not unusual for the nest boxes that researchers install as habitat for the amphibians to get washed away or blocked by sediment. But last spring, Diaz made a startling discovery when she went to check on the animals. Although all of the nearly 100 boxes she’d installed several months earlier in the Little Tennessee River watershed were still in place, not one housed a hellbender. Closer investigation revealed the population was gone.

Hellbenders inhabited these streams as recently...

This population’s disappearance is just one of the latest blows for the salamanders, whose numbers are believed by researchers to be in decline across their range from New York to Alabama and Mississippi and as far west as Missouri. To the surprise of many biologists and conservationists, however, the US Fish and Wildlife Service in April denied the eastern hellbender (C. alleganiensis alleganiensis) federal protection under the Endangered Species Act. The agency cited a paucity of data: there wasn’t enough information available about the past and current status of hellbenders to make an informed assessment.

Diaz, along with her advisor, Clemson University ecologist Cathy Bodinof Jachowski, is working to address this data deficiency while investigating what’s causing hellbender populations to suffer. For example, Jachowski recently completed a study examining how land use upstream from hellbender habitat influences abundance and survival of the animals (Biol Conserv, 220:215–27, 2018). She found that forest cover in the upstream watershed was associated with more hellbenders downstream.

When a stream is full of sediment, and water quality declines, it’s not just hellbenders that suffer.

—Cathy Bodinof Jachowski, Clemson University

What’s more, in heavily forested watersheds, hellbenders were not only more abundant, but their populations showed higher rates of reproduction and greater numbers of young animals reaching adulthood. “It seems that animals in degraded watersheds have trouble reproducing, or young animals are not surviving to adulthood, but we don’t understand the mechanisms of why these occur,” says Jachowski.

Herpetologist Brian Miller of Middle Tennessee State University has also observed declines in hellbender populations. He agrees with Diaz that a decrease in water quality may be a contributing factor, and also proposes a potential role for diseases such as the fungal disease chytridiomycosis. But he emphasizes that “the cause or causes of the declines are unknown.”

To better investigate what’s going on, Jachowski’s laboratory, with funding from the North Carolina Wildlife Resources Commission, is pursuing research into the artificial shelters Diaz used in the Little Tennessee River, both as a monitoring tool and as habitat enhancement. Essentially shoebox-sized concrete containers with a tunnel, these shelters mimic the natural crevices that hellbenders use as homes and nests while also giving researchers easy access via a removable lid on top.

“Lifting rocks is an effective way to find hellbenders, but we’re increasingly aware that it can actually damage the microhabitat beneath,” says Diaz. “With the shelters, we can just lift the lid off to find them instead of altering the habitat they’re using.” Diaz is now comparing different designs to identify which offer the best resilience to disturbances such as flooding, are least likely to be buried by sediment, and are most attractive to home-seeking hellbenders.

The team is also ramping up research on larval hellbenders, which are only two inches long when they leave their natal nest. “Larval ecology of hellbenders is like a black box of research,” says Kirsten Hecht, a doctoral student at the University of Florida and one of the few scientists studying larval hellbenders, although she isn’t involved in the Clemson University group’s work. “We’re trying to conserve this animal, but there are five to seven years of its life that we know very little about.”

Diaz says she and Jachowski hope to identify the resources young hellbenders need, information vital to help guide monitoring efforts, stream restoration attempts, and potential reintroductions. In the meantime, conservation efforts should focus on the animals’ habitat, says Bill Hopkins, an ecologist at Virginia Tech who supervised Jachowski’s PhD. “I think one of the most important things that can be done is addressing landscape-level changes that affect stream quality, sedimentation in streams, and the physical microhabitat of streams,” he says.

Jachowski says that even if people don’t view hellbenders as beautiful creatures the way she does, the amphibians are still valuable as indicators of stream health and water quality. “When a stream is full of sediment, and water quality declines, it’s not just hellbenders that suffer,” she says. “In that sense, hellbenders are a sentinel of environmental quality. If they are declining, that should send off warning bells to all of us.”

Mary Bates is a Boston-based freelance science writer. Follow her on Twitter @mebwriter.

Interested in reading more?