An estimated 9.5 million people all over the world live with type 1 diabetes, wherein the beta cells in their pancreas cannot produce enough insulin to keep blood glucose in check.1 In the long run, elevated glucose can damage organs such as the kidneys, heart, and eyes. Over the past few decades, scientists have been studying how to generate functional insulin-secreting cells which could be transplanted into patients.

Now, researchers led by Xiaofeng Huang, a molecular biologist at Weill Cornell Medical College, engineered human stomach organoids to secrete insulin. Transplanting these into diabetic mice reduced hyperglycemia.2 Their findings, published today in Stem Cell Reports, could help develop technologies to engineer a person’s own insulin-secreting cells for diabetes treatment.

Researchers had previously reprogrammed cells in the mouse stomach and intestine into insulin-producing pancreatic beta-like cells.3,4 Building upon this, Huang and others in the field differentiated human gastric stem cells in vitro into gastric insulin-secreting cells resembling pancreatic beta cells.5 The researchers sought to further explore whether human gastric cells in a complex in vivo environment could similarly differentiate into insulin-secreting cells.

To find out, Huang and his team differentiated human embryonic stem cells into gastric organoids. They engineered the organoids such that the structures could be reprogrammed into pancreatic beta-like cells upon flipping a genetic switch using appropriate molecular cues.

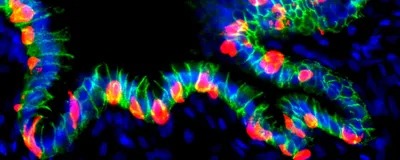

The researchers then transplanted these organoids into the abdomen of mice and coaxed the organoids to produce insulin-secreting cells. Within three weeks, they observed insulin-producing cells within the organoids, which expressed key markers of pancreatic beta cells.

To investigate whether these cells could secrete insulin into the bloodstream and alleviate diabetes, Huang and his team transplanted the organoids into diabetic mice. Insulin secreted from the cells induced from the organoids helped reduce blood glucose and maintain it at normal levels for up to six weeks.

However, this treatment did not help manage hyperglycemia over the long-term in the transplanted mice. Despite this, Huang and his team noted that their results offer a proof of principle that human stomach tissue could be reprogrammed in vivo to generate insulin-secreting cells. This could pave the way for developing an autologous therapeutic strategy wherein cells derived from a diabetic person could be reprogrammed to secrete insulin and transplanted back to manage their type 1 diabetes.

- Ogle GD, et al. Global type 1 diabetes prevalence, incidence, and mortality estimates 2025: Results from the International diabetes Federation Atlas, 11th Edition, and the T1D Index Version 3.0. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2025;225:112277.

- Lu J, et al. Modeling in vivo induction of gastric insulin-secreting cells using transplanted human stomach organoids. Stem Cell Rep. 2025.

- Ariyachet C, et al. Reprogrammed stomach tissue as a renewable source of functional β cells for blood glucose regulation. Cell Stem Cell. 2016;18(3):410-421.

- Chen YJ, et al. De novo formation of insulin-producing "neo-β cell islets" from intestinal crypts. Cell Rep. 2014;6(6):1046-1058.

- Huang X, et al. Stomach-derived human insulin-secreting organoids restore glucose homeostasis. Nat Cell Biol. 2023;25(5):778-786.