|

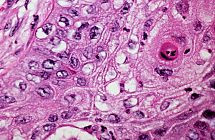

Image: Wikimedia Commons |

**__Related stories:__***linkurl:The science of stress;http://www.the-scientist.com/article/display/55118/

[1st November 2008]*linkurl:Stress and cancer: going with the gut;http://www.the-scientist.com/article/display/14513/

[15th March 2004]*linkurl:Psychoneuroimmunology finds acceptance as science adds evidence;http://www.the-scientist.com/article/display/17128/

[19th August 1996]