During his PhD, an immunologist at a Harvard Medical School-affiliated research hospital followed what he understood to be best practice: recording his work in an electronic lab notebook (ELN). Then the company behind the software was acquired, and the system changed. Links between experiments broke. Formatting was destroyed. “I lost access to a bunch of analysis results,” he said.

The experience left him wary of relying on ELNs for a basic expectation in science: that the record of an experiment will still be there when it is needed.

That incident is not an isolated cautionary tale. A new study suggests that current ELNs are falling short in fundamental steps of the research process including how experiments are recorded, reused, and understood.1

ELNs Struggle with Researcher Needs

The findings come from a November 2025 survey conducted by Coleman Parkes, a global market research agency, and commissioned by Sapio Sciences, a laboratory informatics software company. It included responses from 150 scientists in the United States and Europe working across biopharma R&D, contract research organizations, clinical diagnostics, and pharmaceutical manufacturing.

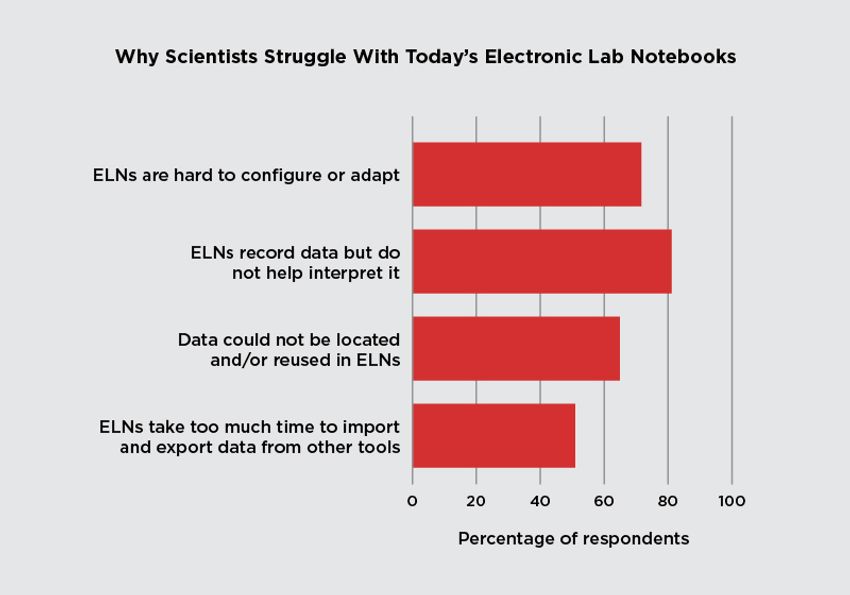

In a recent survey of 150 laboratory scientists in the United States and Europe, 71 percent reported that their electronic lab notebook (ELN) is hard to configure or adapt, 81 percent said their ELN records data but does not help interpret it, 65 percent said they have had to repeat experiments because they could not find or reuse previous results, and 51 percent said they spend too much time importing and exporting data between systems.

Anirban Mukhopadhyay, PhD and Janette Lee-Latour

The survey showed that many scientists struggle to use ELNs as flexible, reusable records of their work. Seventy-one percent said their ELN is hard to configure or adapt to new experiments, and 65 percent reported having to repeat experiments because previous results were difficult to find or reuse. Fifty-one percent said they spend too much time manually importing and exporting data between their ELN and other platforms.

The immunologist, who asked for anonymity due to the requirement of using ELNs at his current institution, said his distrust of ELNs is not tied to any one product. In his own work, he keeps a paper notebook at the bench and a separate digital record for computational analyses, simply scanning and uploading his paper records to the ELN at a later date for institutional compliance.

“The process of recording is abstracted away from the actual experiment,” he said, particularly in wet labs where researchers move constantly between benches, instruments, and computers.

Sayantan Bhattacharya, a cancer systems biologist at the University of Limerick who previously had to use ELNs at MD Anderson Cancer Center, agreed. He described them as frustrating and ill-suited to the way science actually happens, particularly in research that involves troubleshooting, repetition, and frequent changes in direction. In his own work, he said, he avoids relying on ELNs and instead keeps personal records and analyzes data in specialized software, which he later organizes for publication.

Echoing the survey’s findings on ELN inflexibility, the immunologist said many scientists end up “weeks behind” in updating their ELNs, trying to reconstruct experiments long after the fact. That delay, he argued, increases the risk that details will be forgotten or misrecorded, undermining the ELN’s role as a faithful account of what actually happened.

AI as a Workaround—And a Risk

When ELNs prove difficult to adapt or use as working records, there are downstream effects. The survey results suggest that many scientists look for ways to do their planning and analysis outside those systems. Forty-five percent of respondents said they use public generative AI tools through personal accounts to help interpret results and plan next steps—tasks their ELNs cannot easily support. Ninety-six percent agreed that future ELNs should help interpret data, and 95 percent want conversational interfaces.

Rob Brown, head of the scientific office at Sapio Sciences, said this kind of ungoverned AI use creates security, intellectual property, and compliance risks for institutions, stating that when an AI tool is not available within approved lab environments, “people will find it elsewhere.”

For the immunologist, the issue is not whether AI can assist scientific work, but what role a lab notebook should play in the first place. “They’re bad at the job they're supposed to do, not that they fail at the job that I'm supposed to do,” he said.

Brown argued that AI does not need to replace scientific judgment to be useful inside a lab notebook. Features such as voice input and guided workflows, he said, could help scientists document work as it happens. “It’s like having an entire project team in the room with you,” he said.

Bhattacharya warned that AI-driven interpretation can become a black box, where conclusions appear without clear visibility into how they were reached. Such opacity, he said, risks dulling scientific judgment rather than supporting it.

Researchers echoed that concern in the survey results: 81 percent of respondents said they would only trust AI-generated suggestions in an ELN if they could review the underlying science and evidence behind them.

Speaking to the utility of ELNs overall, the immunologist highlighted that the only researchers he knows who are broadly comfortable using ELNs are colleagues in industry, where lab work is often highly routine. When experiments follow the same basic structure week after week, he said, it is easy to rely on fixed templates and fill in variables. That kind of workflow, he said, does not reflect the more exploratory, heterogeneous experiments common in academic biology research.

Brown thinks this next generation of ELNs, designed to actively support analysis and decision-making rather than simply record results, can address some of the limitations scientists now face. Whether such systems can truly accommodate the exploratory and non-routine work common in university-based research labs, however, remains an open question.

- Sapio Sciences. The Rise of the AI Lab Notebook (AILN). 2026.