|

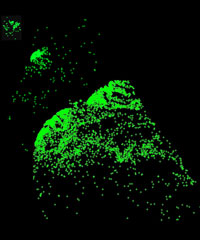

after SIV exposure. Green crosses: clusters of infected cells. Image: A. Haase |

**__Related stories:__***linkurl:HIV microbicide by 2010?;http://www.the-scientist.com/article/display/22293/

[16th July 2004]*linkurl:Topical control of HIV transmission;http://www.the-scientist.com/article/display/13372/

[11th November 2002]