More than 200,000 children succumb to viral gastroenteritis infections, or stomach flu, all over the world every year.1 Human astroviruses are a common cause of such infections, leading to diarrhea, nausea, vomiting, fever, and abdominal pain. However, the viruses are not well-characterized, hampering strategies to prevent and treat viral infection.

Now, scientists led by Rebecca DuBois, a biomolecular engineer at the University of California, Santa Cruz, uncovered the molecular interactions that human astroviruses employ to enter and infect the body.2 Their findings, published in Nature Communications, could inform the design of human astrovirus vaccines and antibody therapies.

“We uncovered a really important part of the virus lifecycle, and now we know exactly where on the virus this important interaction with the human receptor occurs,” said DuBois in a press release. “Now we can develop vaccines that will target it and block that interaction—it really guides future vaccine development.”

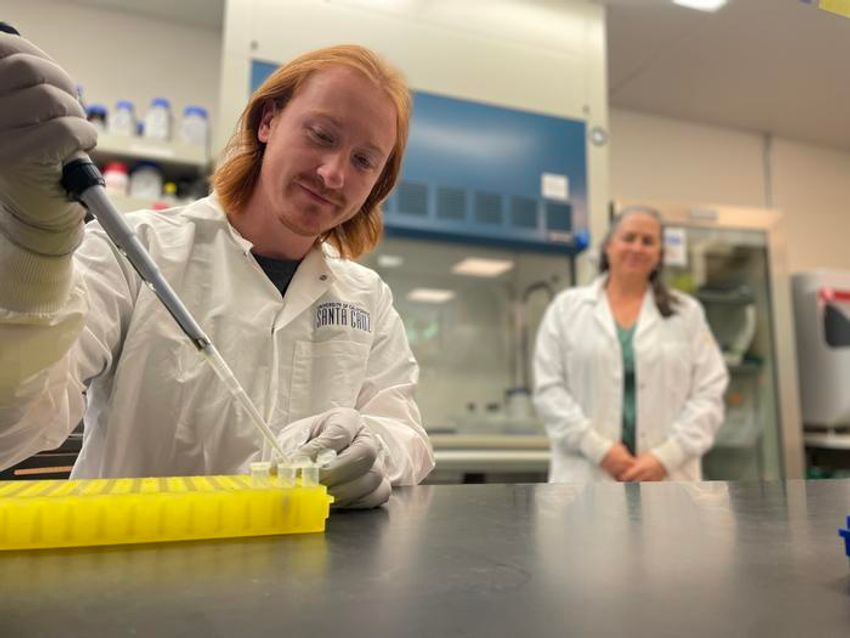

Adam Lentz, a graduate student in Rebecca DuBois’s lab at UC Santa Cruz led a project to better understand the structure of human astroviruses.

Rebecca DuBois/ UC Santa Cruz

Last year, using cultured intestinal cells and intestinal organoids, scientists discovered that spike proteins on human astroviruses bind to the neonatal Fc receptor (FcRn), which transports antibodies in the gastrointestinal tract.3,4 However, the exact molecular interactions between the virus and the receptor remained unknown.

To investigate this, DuBois and her team generated recombinant FcRn and human astrovirus 1 spike proteins and allowed them to bind. X-ray crystallography of the protein complex revealed three crucial amino acid residues on the viral protein that interacted with the receptor. Mutating these reduced the binding between FcRn and the viral protein, highlighting the importance of these amino acid residues.

The crystal structure further revealed that the virus binds to the same site on the receptor that antibodies bind to for getting transported within the gastrointestinal tract. “The virus is hijacking the pathway that humans use for beneficial purposes to get inside the cell,” said DuBois. “I think that’s one of the most exciting findings—we discovered exactly how the virus is using this receptor to sneak into our cells.”

An FDA-approved drug called Nipocalimab—prescribed for the treatment of myasthenia gravis—binds to the antibody-binding site on the FcRn. Viral spike protein failed to bind to FcRn that had been preincubated with Nipocalimab, suggesting that the drug could potentially be repurposed to treat human astrovirus infections.

- Stuempfig ND, et al. Viral gastroenteritis. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2025 Jan-.

- Lentz A, et al. Structure of the human astrovirus capsid spike in complex with the neonatal Fc receptor. Nat Commun. 2025;16(1):9621.

- Haga K, et al. Neonatal Fc receptor is a functional receptor for classical human astrovirus. Genes Cells. 2024;29(11):983-1001.

- Ingle H, et al. The neonatal Fc receptor is a cellular receptor for human astrovirus. Nat Microbiol. 2024;9(12):3321-3331.