As Halloween and other indulgent holidays come up on the calendars, people are likely to enjoy more sweet treats. But it won’t only be the individual enjoying that extra rush of sugar; the bacteria that call the human mouth home will also be responding to the additional candies and confectionary creations. So how does the oral microbiome respond to sugar?

“In the most worst possible ways,” answered Purnima Kumar, a clinician scientist and periodontist who studies the oral microbiome at University of Michigan.

Kumar described a healthy, oral microbiome as a community that uses oxygen for its energy production. “Because it's energy efficient it does not produce a lot of toxins or metabolic byproducts,” she said. “That's what our immune system recognizes as health compatible and therefore literally lives in harmony with it or tolerates it.”

Purnima Kumar studies how the oral microbiome interacts with the host immune system to promote health and how disruptions to this balance leads to disease.

Osteology Foundation

In addition to regular brushing and flossing, Kumar said that diet has a large influence on the microbiome. Less processed foods, especially those high in fiber, are often less sticky, which decreases bacteria’s ability to adhere and overgrow at a surface. Additionally, the fiber acts like miniature brushes. “These fibers constantly remove this plaque from your tooth surfaces,” Kumar said. The additional chewing of these types of foods also increases saliva production, which washes out the oral cavity, removing excess bacteria from the mouth surface to limit the formation of biofilms.1,2

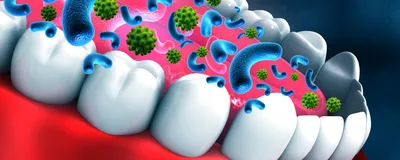

Meanwhile, additional sugar from candy and other sweet products disrupts this whole community. Not only are these processed foods stickier, giving the bacteria a place to latch onto, but they also form biofilms, explained Kumar.3

Excess sugar also stresses the bacteria. “Microbial communities actually respond to stress [or] express stress by cloaking themselves in this thick slimy layer,” Kumar said. “Our immune system sees slime layer and thinks ‘I need to get rid of this.’”

In addition to the inflammatory response that ensues, the bacteria also undergo fermentation; this in turn leads to the production of acid byproducts that degrade tooth enamel, which causes cavities, and further trigger the immune system.2 Overtime, this environment shifts the microbial diversity, favoring bacteria that can survive acidic conditions.4 If left unchecked, this microbial shift and inflammatory damage can give rise to periodontal disease.1,5

These effects, like developing cavities, aren’t just influenced by the total amount of sugar a person eats.6 “Frequency of intake is as important if not more important than amount of intake,” Kumar said.

According to her, the best thing to do to reduce the effects of sugar stress in the oral cavity is to eat the sweets at one time as opposed to throughout the day. Additionally, “If you have to eat sweets, then make sure you brush and you remove all vestiges of it from all the different crevices in your teeth that [the sugar] can sit on and stay on.”

- Santonocito S, et al. A cross-talk between diet and the oral microbiome: Balance of nutrition on inflammation and immune system’s response during periodontitis. Nutrients. 2022;14(12):2426.

- Marsh PD. Microbial ecology of dental plaque and its significance in health and disease. Adv Dent Res. 1994;8(2):263-271.

- Koo H, et al. The exopolysaccharide matrix: A virulence determinant of cariogenic biofilm. J Dent Res. 2013;92(12):1065-1073.

- Angarita-Díaz MDP, et al. Does high sugar intake really alter the oral microbiota?: A systematic review. Clin Exper Dent Res. 2022;8(6):1376-1390.

- Shanmugasunduram S, Karmakar S. Excess dietary sugar and its impact on periodontal inflammation: A narrative review. BDJ Open. 2024;10(1):78.

- Head D, et al. In silico modelling to differentiate the contribution of sugar frequency versus total amount in driving biofilm dysbiosis in dental caries. Sci Rep. 2017;7(1):17413.