While the world was busy solving Rubik’s Cubes and marveling over Doc Brown’s DeLorean time machine in the 1980s, scientists began noticing a peculiar relationship between dental health and heart disease. Individuals who suffered myocardial infarctions—commonly known as heart attacks—or had chronic coronary heart disease had higher levels of antibodies against infectious bacteria and had more dental infections compared to healthy counterparts.1 This gave way to the idea that bacterial infections might cause chronic inflammation of arterial blocks, a key risk factor for cardiac events. “Everybody thought that we can solve this myocardial infarction problem by giving patients antibiotics,” said Pekka Karhunen, a physician-scientist at Tampere University who studies the link between oral bacteria and cardiovascular health. However, most clinical trials failed to reduce the cardiac risk.2 “So, the infection hypothesis was forgotten for 20 years,” Karhunen said.

Pekka Karhunen is a physician-scientist at Tampere University who studies the link between oral bacteria and cardiovascular health.

Pekka Karhunen

Now, after almost four decades, Karhunen and his colleagues reported that hardened cholesterol plaques in arteries may harbor oral bacteria encased in a biofilm, thus making them impervious to antibiotics and the body’s immune system.3 “It's not the bacteria themselves but the response by the host that starts to destroy the structures that lead to myocardial infarction,” Karhunen said. These findings, published in the Journal of the American Heart Association, open avenues for the development of new biofilm-targeted ways to diagnose and prevent heart attacks.

“This is quite intriguing,” said Stanley Hazen, a cardiologist at the Cleveland Clinic who was not involved in the study. “It's another piece of evidence that argues for a potential infectious cause to cardiovascular disease risk.”

What inspired Karhunen to shake the dust off the infection hypothesis after decades? In 2005, a colleague working on bacterial DNA detection approached Karhunen, who worked as a forensic pathologist at the time, for samples of coronary artery plaques, or atheromas. Using bacterial DNA amplification methods, the researchers found that the atheromas contained genetic material from viridans streptococci, a prevalent group of commensal bacteria found in the oral microbiome, among various other species. “We were quite surprised,” Karhunen said. “We thought that we have made some mistake in the autopsy room.”

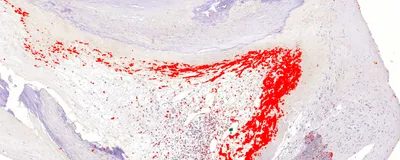

To understand the effects of bacteria on the atheromas more deeply, Karhunen and his colleagues studied arterial plaques obtained from 121 sudden death victims and 96 surgical patients. Quantitative PCR experiments revealed that 65 percent of the sudden death plaque samples and 58 percent of the surgical plaques had DNA from oral viridans streptococci, mainly Streptococcus mitis. To determine the presence of actual bacteria—not just their DNA—the researchers stained the samples using antibodies against three of the most common viridans streptococci and observed that more than half of the sudden death and surgical samples showed presence of bacteria within the core of the plaques. When they co-stained the plaques with a macrophage biomarker, they observed that the immune cells did not detect the bacterial clumps inside the atheromas, indicating that the bacteria were encased in a biofilm. “I almost fell off my chair,” Karhunen said.

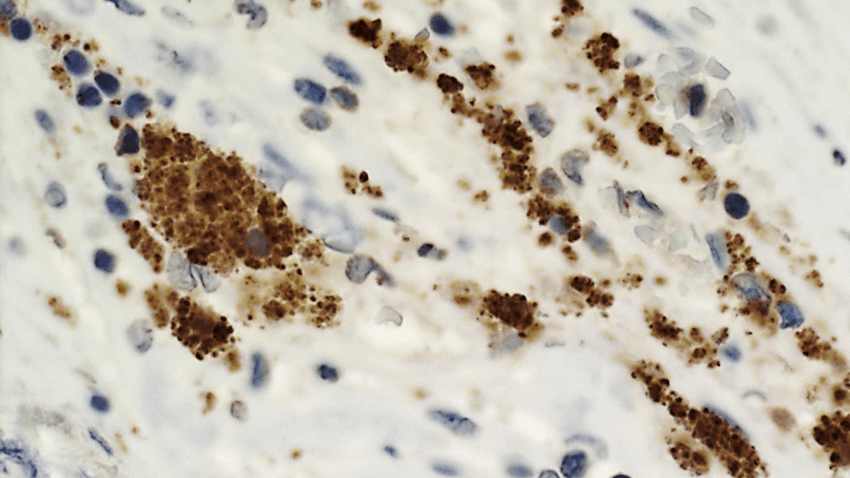

Bacteria within biofilms can lay dormant in arterial plaques for years, until a trigger activates them, possibly leading to a myocardial infarction. Shown here are streptococci bacteria (brown) in the wall of a ruptured coronary plaque.

Pekka Karhunen

Next, the researchers analyzed ruptured plaques, which cause myocardial infarctions, and observed staining for streptococci that appeared to have originated from the biofilm infiltrating the rupture site and that were then engulfed by macrophages. Using genome-wide expression analysis of the surgically removed arterial plaques, Karhunen and his colleagues also observed an upregulation of immune pathways for recognizing and killing bacteria compared to healthy arteries. “You would not expect to see the type of immune responses that were observed at the sites of plaque rupture if it happened postmortem,” Hazen said.

But how exactly did the bacteria enter and thrive inside these oxygen-deficient atheromas? The team observed the presence of new blood vessels feeding the core of the plaques, forming a direct highway for bacteria to enter and set up camp inside these structures.

Karhunen and his team now want to understand why biofilm bacteria start dividing again. They speculate that an external trigger, such as a viral infection or limited nutrition, might lead to proliferation of the bacteria and subsequent immune response. Using viral metagenomics, they’re analyzing all possible viruses present in the plaque samples to ascertain if there might be a possible link between viral infections and plaque rupture. The researchers are also starting a new antibiotic trial to treat myocardial infarctions. “If we start antibiotics treatment immediately, it might affect the outcome of these patients,” Karhunen said.

Hazen emphasized the huge burden of heart disease worldwide and the underappreciated role of oral hygiene in cardiac risk. “Anything that casts more light on that and the whole concept of preventive cardiology is an important message,” he said.

- Saikku P, et al. Serological evidence of an association of a novel chlamydia, TWAR, with chronic coronary heart disease and acute myocardial infarction. Lancet. 1988;332(8618):983-986.

- Cannon CP, et al. Antibiotic treatment of Chlamydia pneumoniae after acute coronary syndrome. New Eng J Med. 2005;352(16):1646-1654.

- Karhunen PJ, et al. Viridans streptococcal biofilm evades immune detection and contributes to inflammation and rupture of atherosclerotic plaques. J Am Heart Assoc. 2025;14(16):e041521.