THE SCOPE: Imperfections known as nitrogen vacancies (NVs) in a diamond’s carbon lattice absorb green laser light and emit red light. The brightness of this emitted light is affected by nearby magnetic fields, such as those present in magnetotactic bacteria. A camera mounted on the microscope captures the emitted light and, thus, the magnetic fields of the bacteria.© LUCY READING-IKKANDASome bacteria build intracellular nanoscale magnets and use them to travel by orienting themselves to the Earth’s magnetic lines. Researchers are interested in these magnet-building microbes (who wouldn’t be?) not just because they might have implications for higher organisms that use magnetically guided migration, but also because such magnetic nanoparticles could have medical applications. They might be used to enhance the contrast of patients’ cells in MRI images, for example, or even to kill cancers.

THE SCOPE: Imperfections known as nitrogen vacancies (NVs) in a diamond’s carbon lattice absorb green laser light and emit red light. The brightness of this emitted light is affected by nearby magnetic fields, such as those present in magnetotactic bacteria. A camera mounted on the microscope captures the emitted light and, thus, the magnetic fields of the bacteria.© LUCY READING-IKKANDASome bacteria build intracellular nanoscale magnets and use them to travel by orienting themselves to the Earth’s magnetic lines. Researchers are interested in these magnet-building microbes (who wouldn’t be?) not just because they might have implications for higher organisms that use magnetically guided migration, but also because such magnetic nanoparticles could have medical applications. They might be used to enhance the contrast of patients’ cells in MRI images, for example, or even to kill cancers.

Now, for the first time, studying magnetic fields at high resolution inside living bacteria is possible, thanks to a gem of an idea from Ronald Walsworth, a physics professor at Harvard University, and colleagues.

THE CHIP: An NV consists of a nitrogen atom (N) adjacent to a vacancy (V) in the diamond’s carbon (C) lattice.© LUCY READING-IKKANDAThe key is diamonds, or, to be precise, imperfections in diamonds called nitrogen vacancies (NVs). NVs are disruptions to the diamond’s carbon atom lattice whereby two neighboring carbons are replaced with a single nitrogen atom and an adjacent gap. Importantly, these NVs have a couple of properties that make them perfect for magnetic imaging, explains Walsworth. First, their associated electrons have a particular way of spinning that is affected by nearby magnetic fields. Second, NVs absorb green light and emit red light, the intensity of which increases or decreases in relation to the spin of their electrons. Magnetic fields emitted by the bacteria would therefore affect the spinning electrons, resulting in a dimming or brightening of the red light.

THE CHIP: An NV consists of a nitrogen atom (N) adjacent to a vacancy (V) in the diamond’s carbon (C) lattice.© LUCY READING-IKKANDAThe key is diamonds, or, to be precise, imperfections in diamonds called nitrogen vacancies (NVs). NVs are disruptions to the diamond’s carbon atom lattice whereby two neighboring carbons are replaced with a single nitrogen atom and an adjacent gap. Importantly, these NVs have a couple of properties that make them perfect for magnetic imaging, explains Walsworth. First, their associated electrons have a particular way of spinning that is affected by nearby magnetic fields. Second, NVs absorb green light and emit red light, the intensity of which increases or decreases in relation to the spin of their electrons. Magnetic fields emitted by the bacteria would therefore affect the spinning electrons, resulting in a dimming or brightening of the red light.

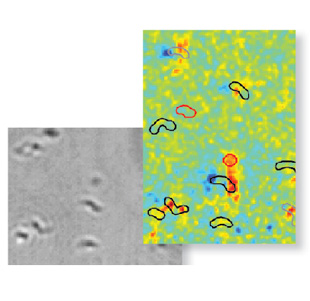

THE IMAGES: The microscope captures both regular light images (above left) and magnetic images (above right) of the same live bacteria (outlined in the above right image).IMAGES COURTESY OF DAVID LE SAGEWalsworth and colleagues have constructed a microscope in which living magnetotactic bacteria placed on an NV-containing diamond chip can be viewed under both normal light conditions and under conditions that detect the bacteria’s magnetic fields—via the diamond’s emitted red light. “The new technique will be excellent” for figuring out the biological pathways controlling magnetic particle growth in these bacteria, says Mihály Pósfai, a magnetotactic bacteria expert at the University of Pannonia in Hungary. (Nature, 496:486-89, 2013)

THE IMAGES: The microscope captures both regular light images (above left) and magnetic images (above right) of the same live bacteria (outlined in the above right image).IMAGES COURTESY OF DAVID LE SAGEWalsworth and colleagues have constructed a microscope in which living magnetotactic bacteria placed on an NV-containing diamond chip can be viewed under both normal light conditions and under conditions that detect the bacteria’s magnetic fields—via the diamond’s emitted red light. “The new technique will be excellent” for figuring out the biological pathways controlling magnetic particle growth in these bacteria, says Mihály Pósfai, a magnetotactic bacteria expert at the University of Pannonia in Hungary. (Nature, 496:486-89, 2013)

![]()