Researchers have identified the function of an obscure but large family of proteins whose function in cellular immune responses had been unknown.  |

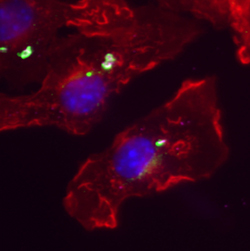

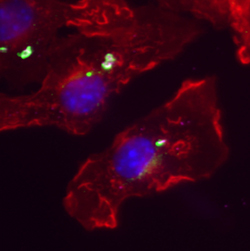

Fluorescent micrograph of Gbp1 (green) targeting mycobacteria (magenta rods) in interferon-activated macrophages (red, actin staining;

blue, nuclear staining)

Image courtesy of John MacMicking |

Microbiologist John MacMicking shows how specialized proteins

battle bacteria inside immune cells.

Video courtesy of Science and John MacMicking

**__Related stories:__***linkurl:Cellular chaos fights infection;http://www.the-scientist.com/news/display/57982/

[10th February 2011] *linkurl:RNA Arms Race;http://www.the-scientist.com/2010/8/1/51/1/

[1st August 2010] *linkurl:Antiviral response promotes bacterial infection;http://www.the-scientist.com/news/display/25036/

[10th October 2006]