Kidney stones can be excruciatingly painful in humans, but for birds and reptiles, peeing solids is just part of the daily grind.

Scientists have studied this phenomenon for centuries, but the structure, composition, and properties of these solids eluded them. To close this gap, Jennifer Swift, a chemist at Georgetown University, and her colleagues chemically characterized these wastes in over 20 types of snakes.1 Their findings, published in the Journal of the American Chemical Society, offer insights into how this waste management system evolved in some organisms.

“This research was really inspired by a desire to understand the ways reptiles are able to excrete this material safely, in the hopes it might inspire new approaches to disease prevention and treatment,” said Swift in a statement.

When animals metabolize proteins and nucleotides, they produce excess nitrogen, which typically leaves the body in the forms of ammonia, urea, or uric acid. Humans and other mammals excrete urea diluted in large volumes of water (urine), which also contains small amounts of ammonia and uric acid. When the level of uric acid gets too high, it can crystallize in the body, forming kidney stones. On the other hand, birds, reptiles, and some insects excrete uric acid in solid form, which are often called urates.

Swift and her colleagues previously investigated urates from eight species of snakes, comparing between primitive, non-venomous snakes, such as boas and pythons, and advanced, venomous snakes, such as rattlesnakes.2 The researchers fed the snakes a controlled laboratory-mice diet, then analyzed their urates.

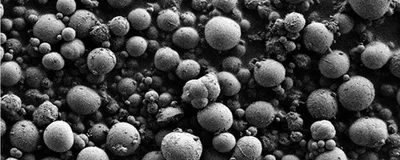

The team observed differences in when the snakes excreted urates as well as how the dried urates looked. The primitive snakes first excreted urates alone three to seven days after feeding, then alongside feces between days seven to 15. On the other hand, advanced snakes only excreted urates once, with feces, between six to 10 days after they ate. Furthermore, the primitive snakes' urates dried to hard pellets, while those of their advanced counterparts formed granular dust. Because of these differences, the researchers hypothesized that primitive and advanced snakes handled their waste using unrelated mechanisms.

In the present study, Swift’s team investigated urates from about twice as many snake species of both types, primitive and advanced. As in the previous study, they observed clear differences in urate excretion in primitive versus advanced snakes.

Despite these differences, microscopy revealed that both urates contained microspheres as well as crystals, though there were much fewer of these structures in the advanced snakes’ urates. This indicated that, in contrary to what the researchers had expected, the same waste management system is shared across primitive and advanced snakes.

Using an X-ray diffraction method, the team found that the microspheres, the main structures in the primitive snakes’ urates, mostly consisted of uric acid monohydrate (UAM). They hypothesized that in advanced snakes, UAM sequesters ammonia to form ammonium urate, the main constituent of the advanced snakes’ urates. Sequestering ammonia into a solid form likely reduces the possibility of the snakes’ bodies contacting the toxic chemical as they slither on the ground, the researchers proposed.

To test this hypothesis, the researchers immersed primitive snake urates into aqueous ammonium hydroxide. They observed that the granular form of advanced snakes’ urates readily formed, and its X-ray diffraction profile closely resembled that of advanced snakes’ urates. These results were consistent with the team’s hypothesis that UAM is a vital molecule to manage toxic waste and excrete urates, at least in snakes.

In the future, Swift and her team hope to understand how and where UAM microspheres form in urate-excreting animals. This knowledge may provide novel insights into how different organisms, even humans, detoxify their toxic metabolic byproducts.

- Thornton AM, et al. Uric acid monohydrate nanocrystals: An adaptable platform for nitrogen and salt management in reptiles. J Am Chem Soc. 2025.

- Thornton AM, et al. Urates of colubroid snakes are different from those of boids and pythonids. Biol J Linn Soc. 2021;133(3):910-919.