It’s a typical day at the general practitioner’s office. As the street bustles with activity, a patient walks in, complaining of pain in his bladder, frequent urination, and a burning sensation while peeing. All signs point to a urinary tract infection. As protocol dictates, the doctor orders a urine test to check for bacterial infection and to know which antibiotic will work best to clear it up. But she knows that she won’t receive results for several days or weeks. In the meantime, she prescribes a broad-spectrum antibiotic that will indiscriminately kill all sensitive microbes in the patient’s body. However, certain resistant bacteria might survive and flourish.

This is a common scenario in many countries. Studies conducted in the UK, USA, India, and South Africa, among others, reported unnecessary use of broad-spectrum drugs in 30 to 95 percent of patients with signs of bacterial infections.1,2 This practice, along with the unregulated overuse of antibiotics in the livestock industry, are the major drivers of the silent pandemic called antimicrobial resistance (AMR), that kills millions of people every year.3

Andreas Güntner is a mechanical engineer at ETH Zurich who develops new technologies to tackle healthcare and environmental issues.

Andreas Güntner

“This is a problem we have to solve,” said Andreas Güntner, a mechanical engineer at the Swiss Federal Institute of Technology (ETH), Zurich who develops new technologies for biomedical research. “If the effectiveness of antibiotics deteriorates at the same speed as it is right now, we may go back to medicine 300 years ago, where people just died from a simple infection.”

The current diagnostic workflow to detect AMR is long and requires specialized and expensive equipment. Slow detection methods push healthcare professionals to rely on non-specific treatments that end up doing more harm than good in the long run. “What we need are rapid and easily usable diagnostic tools,” Güntner said.

Inspired by this dire need to slow down AMR and the World Health Organization’s initiative to strengthen the global AMR diagnostic capacity, Güntner and his colleagues proposed using tiny gas sensors to sniff out bacterial infections and detect AMR in bodily fluids.4 The envisioned method, published in Cell Biomaterials, could shorten the time needed to identify the infectious strain of bacteria and its sensitivity to antibiotics, from days to mere minutes.

Smells Like Trouble: The Scent of AMR

Doctors have relied on their noses to detect bacterial infections for ages. Pseudomonas aeruginosa smells like grapes, Streptococcus anginosus gives off a caramel aroma, and Clostridium species have a putrid stench.5–7 “Since the times of Hippocrates or Avicenna, physicians knew that the foul smell from infected wounds or the sulfuric smell from halitosis in the teeth meant something,” said Mehmet Bilgin, a graduate student in Güntner’s lab and coauthor of the perspective.

Mehmet Bilgin is a doctoral student in Andreas Güntner’s lab at ETH Zurich, where he develops gas sensors for diagnosing bacterial infections and antimicrobial resistance.

Mehmet Bilgin

These distinctive odors arise from bacterial volatile organic compounds (VOCs), which are products of various microbial metabolic activities. Many processes like ammonia production from degrading proteins or ethanol synthesis from sugar fermentation are common across genera and species. However, certain odor biomarkers could help to identify specific strains, their virulence and AMR.8 “With the development of high-resolution mass spectrometers and other analytical tools, we can accurately determine the composition and concentration of smell molecules,” Bilgin said. Using such tools, researchers in the UK have detected a combination of six VOCs to differentiate antibiotic resistant and susceptible strains of Escherichia coli with 85 percent accuracy.9

Güntner and his team previously developed sensors to detect ammonia, acetone, isoprene, and other gaseous compounds in breath, that have potential to monitor various human diseases.10–12 Inspired by the group’s work, Adrian Egli, a medical microbiologist at ETH Zurich, approached Güntner at a barbeque party with the idea of building gas sensors to spot AMR. “If you detect diseases from breath, why can't you also sniff the breath of bacteria?” he said to Güntner. Soon, the discussion drew attention from other researchers at the institute: Thomas Kessler, a neuro-urologist; Emma Slack, an immunologist; and Catherine Jutzeler, a data scientist. “We thought that it would be a great idea to utilize the synergies between clinicians, engineers, and machine learning experts,” Güntner said.

A Nose for AMR

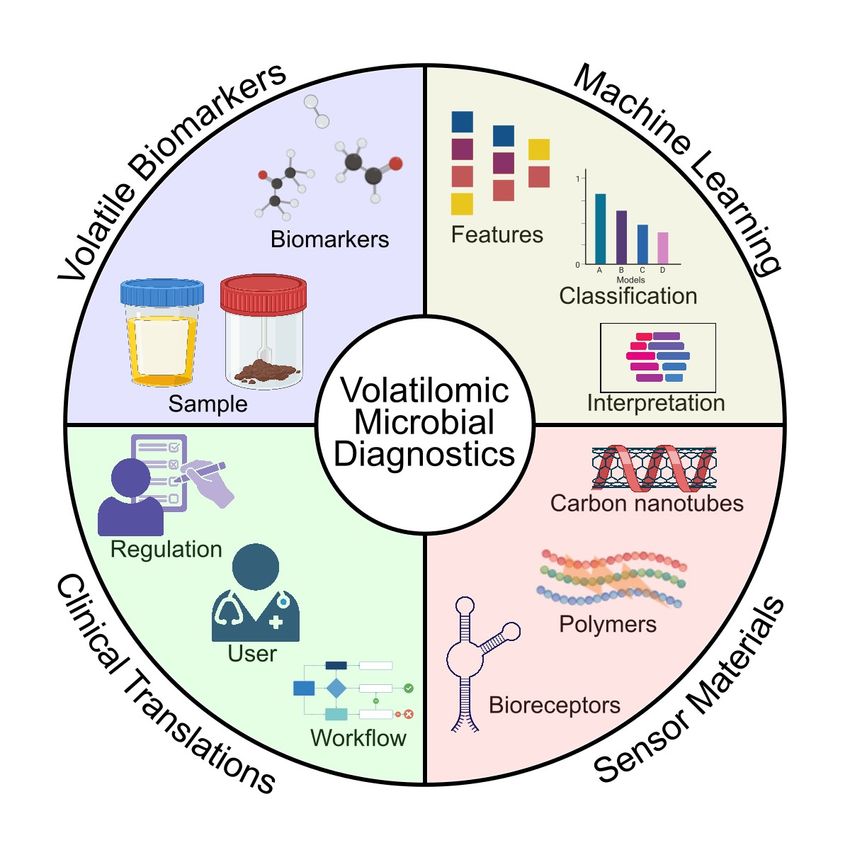

The multi-disciplinary team came up with a brand-new diagnostic process to identify microbes and their antibiotic sensitivities based on the VOCs in the headspace above a sample of urine. A key component for accurate strain detection is knowledge about volatile-based biomarkers. Güntner and his colleagues plan to use machine learning algorithms to condense the complex profiles of bacterial VOCs into a set of biomarkers that can aid the detection of microbial species, their AMR status, and virulence profiles.

Researchers are developing a method that combines machine learning and sensor technology to sniff out infectious and drug-resistant bacteria. This volatile-based diagnostics could reduce overuse of broad-spectrum antibiotics.

Bilgin et al., Cell Biomaterials, 2025.

The next step is to develop compact sensors that can reliably detect volatile biomarkers. The challenge is that they must also be sensitive to the faint concentrations of relevant VOCs. Consider a room full of one million blue balls and just one red ball. That’s the relative concentration of VOCs the sensors need to capture within seconds. “The secret to why you can detect such low concentration is because of the immense surface area of the nanoparticles on the sensors,” Güntner explained. “One teaspoon of these nanoparticles has more than 100 square meters of surface area.”

The next obstacle is to make sure the sensor only detects the relevant biomarker and not the hundreds of other VOCs in the bacterial headspace. Diverse materials like metal oxides, polymers, graphene derivatives, and carbon nanotubules could capture all these requirements and make good sensors.

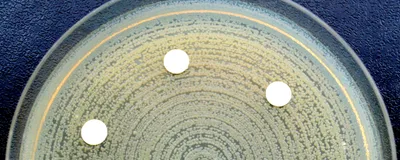

Bilgin has already built a device that can differentiate between a plate with and without bacterial growth, solely based on the volatile compounds. “This was really exciting for me,” he said.

The team plans to come up with the first prototype to detect E. coli in the next three years. Currently, the frequency of bacteriological testing is as low as 1.3 percent in certain resource-poor parts of the world. Güntner and his colleagues hope that with the implementation of their technology, that number goes up, thus reducing the overuse of antibiotics and easing the burden of AMR. Not only will the device be compact, but could be operated by non-trained personnel, improving its implementation in remote corners of the world.

“In a decade or two, when hopefully there are effective solutions in place and antimicrobial resistance is less of an issue, we can say we contributed to it. We made a big leap. At the end of the day, that’s what we all dream about,” Güntner said.

- Brenon JR, et al. Rate of broad-spectrum antibiotic overuse in patients receiving outpatient parenteral antibiotic therapy (OPAT).Antimicrob Steward Healthc Epidemiol. 2021;1(1):e36.

- Markham JL, et al. Outcomes associated with initial narrow-spectrum versus broad-spectrum antibiotics in children hospitalized with urinary tract infections.J Hospital Med. 2024;19(9):777-786.

- Reghukumar A. Drivers of antimicrobial resistance. In: Handbook on Antimicrobial Resistance. Springer, Singapore; 2023:1-16.

- Bilgin MB, et al. Microbial and antimicrobial resistance diagnostics by gas sensors and machine learning.Cell Biomater. 2025;1(7):100125.

- Cox CD, Parker J. Use of 2-aminoacetophenone production in identification of Pseudomonas aeruginosa.J Clin Microbiol. 1979;9(4):479-484.

- Chew TA, Smith JM. Detection of diacetyl (caramel odor) in presumptive identification of the “Streptococcus milleri” group.J Clin Microbiol. 1992;30(11):3028-3029.

- Stevens DL, et al. Clostridium. In: Manual of Clinical Microbiology. John Wiley & Sons, Ltd; 2015:940-966.

- Kemmler E, et al. mVOC 4.0: A database of microbial volatiles.Nucleic Acids Res. 2025;53(D1):D1692-D1696.

- Hewett K, et al. Towards the identification of antibiotic-resistant bacteria causing urinary tract infections using volatile organic compounds analysis—A pilot study.Antibiotics. 2020;9(11):797.

- Güntner AT, et al. Selective sensing of isoprene by Ti-doped ZnO for breath diagnostics.J Mater Chem B. 2016;4(32):5358-5366.

- Güntner AT, et al. Noninvasive body fat burn monitoring from exhaled acetone with Si-doped WO3-sensing nanoparticles.Anal Chem. 2017;89(19):10578-10584.

- Güntner AT et al. Selective sensing of NH3 by si-doped α-MoO3 for breath analysis.Sens Actuators B Chem. 2016;223:266-273.