In 2009, “master virus hunter” Ian Lipkin, an experimental pathologist at Columbia University who has identified more than 2,500 viruses and contributed containment strategies during several major viral outbreaks, received a curious phone call. Screenwriter Scott Burns wanted his help to write a movie about a pandemic. Although interested in this unique opportunity, Lipkin, a stickler for scientific accuracy, recalled saying, “I’m only going to do this if it’s going to be informative and interesting.” Burns replied, “That’s exactly what we wanted to do.” Thus began Lipkin’s Contagion journey.

From Contagion to Contagion

Burns initially reached out to Larry Brilliant, an epidemiologist and chief executive officer of the Pandefense Advisory, after seeing a Ted Talk from Brilliant on pandemics. Brilliant had met Lipkin through Pandefense Advisory, and recommended Burns include him as well, leading to Lipkin’s invitation to the set.

Burns and director Steven Soderbergh wanted to create a movie that followed a realistic response to a pandemic. The two had funding through a production company, Participant Media, which created entertainment content that addressed societal issues in key areas, including heath care “[Burns and Soderbergh] really wanted to make something that was going to be educational,” Lipkin said.

Burns wanted Lipkin’s input on potential infectious agents and a realistic pandemic response, given his experience handling the 2003 SARS outbreak. Ultimately, the duo decided on their star pathogen, a paramyxovirus. Then, Burns started writing, sharing drafts with Lipkin to make sure the science checked out. “He wanted to make sure that everything he was proposing was plausible,” Lipkin said.

A year later, they had a solid script for Contagion, a pandemic-response thriller. Their story started with an infected person taking an international flight home while experiencing increasingly severe cold symptoms. When she dies of the mysterious illness, an epidemic intelligence service officer investigates the situation. A full public health response ensues as more people come down with the new illness, meanwhile the Center for Disease Control and Prevention rushes to identify the agent and then develop a vaccine against it and distribute it to the public.

Ian Lipkin provided expertise on scientific details on the set of Contagion, including instructing actors on how scientific techniques would be performed.

Claudette Barius

“I thought I was going to be done helping him with the screenplay,” Lipkin recalled, “but then other people involved with the production started reaching out to me.”

Lipkin found himself advising different departments as production progressed. He helped the set designer create accurate costumes for the film’s characters to wear. He opened his lab to teach two stars a handful of key research skills and let the sound team record the sounds in the room.

“Then, I said, ‘why not take advantage of the situation and try to be on set?’,” Lipkin said. His luck panned out and he joined the filming crew, which turned out to be helpful when the team needed a 3D virus model that Lipkin helped create.

Although Lipkin and the movie team tried their best to ensure scientific accuracy, because of budget and physical constraints, they had to compromise on some elements of filming. Lipkin recalled one scene where a character experiences a seizure. “She’s foaming at the mouth with Alka-Seltzer, which doesn’t look real,” he said.

Wherever possible though, he pushed to make the shots as realistic as possible. In an original take, another character injects a vaccine in her thigh through tights. “I said, ‘Come on guys, we should reshoot this,’” Lipkin recalled. “They actually brought her back. So, she rolled down her tights and she swabbed her leg before she did the injection.”

However, he admitted that his experience and level of involvement in the production was atypical and the result of the unique circumstances behind the movie. While Contagion may have been unique in the involvement of its scientific expert advisors for its script, it’s not alone in seeking researcher input for accuracy in portraying science.

Researcher on Rampage: Science Advisor to Sci-Fi Extra

James Dahlman, a biomedical engineer studying nucleic acid delivery at Georgia Institute of Technology and Emory University, received a phone call asking for his help with a CRISPR movie, he recalled, “My first response was no.” Around that time, media outlets were covering the unethical actions of a scientist who had used CRISPR to genetically alter and then implant two human embryos. “I thought it was going to be some silly YouTube conspiracy video kind of thing,” he said.

However, after learning that the caller represented a legitimate production company making a proper movie, Dahlman heard the pitch. Rampage was a science fiction flick with a CRISPR-conundrum at its heart. A nefarious biotechnology company developed a pathogen that had gene-editing capabilities; when these pathogens wound up in three animals, they mutated into rampaging beasts. One of these was a gorilla raised by a primatologist in a sanctuary. To save his primate friend and the city, this scientist and a gene engineer team up to stop the animals and bring down the corporation (don’t worry, the gorilla lives).

James Dahlman, whose research group uses CRISPR and develops RNA therapeutics, provided scientific advice for the movie Rampage.

Readout Capital

While the script for the movie was already written, “They did ask me some good scientific questions,” Dahlman said. They checked with him whether they set things up correctly or if they explained CRISPR correctly. “Those conversations [were] pretty short because [they’d] done their homework.”

However, the team wanted help creating scenes in a lab, including training actors to perform some tasks, so Dahlman joined the set where a crew recreated a level 2 biosafety laboratory. They had even included pipettes and tips for the actors to use. “But they didn’t know which tips went with them,” he recalled. “The [actors] would just push a pipette into the wrong size pipette and then the pipette tip wouldn’t stick.” Dahlman taught the actors the art of pipetting. “We all take that [skill] for granted, but that’s something that not everybody knows,” he said.

Dahlman also helped the set team organize the laboratory to reflect certain instruments’ actual functions. He provided insights into the types of actions and behaviors that would be typical in a research lab, including wearing gloves to touch reagents and supplies.

“It’s never going to be fully realistic because it’s imaginary. But within that constraint, you want it to be as realistic as it can be,” Dahlman said, adding that he felt like the team accomplished this, and that they incorporated almost any recommendation he made that they feasibly could. “They really wanted those little details to be correct,” he said.

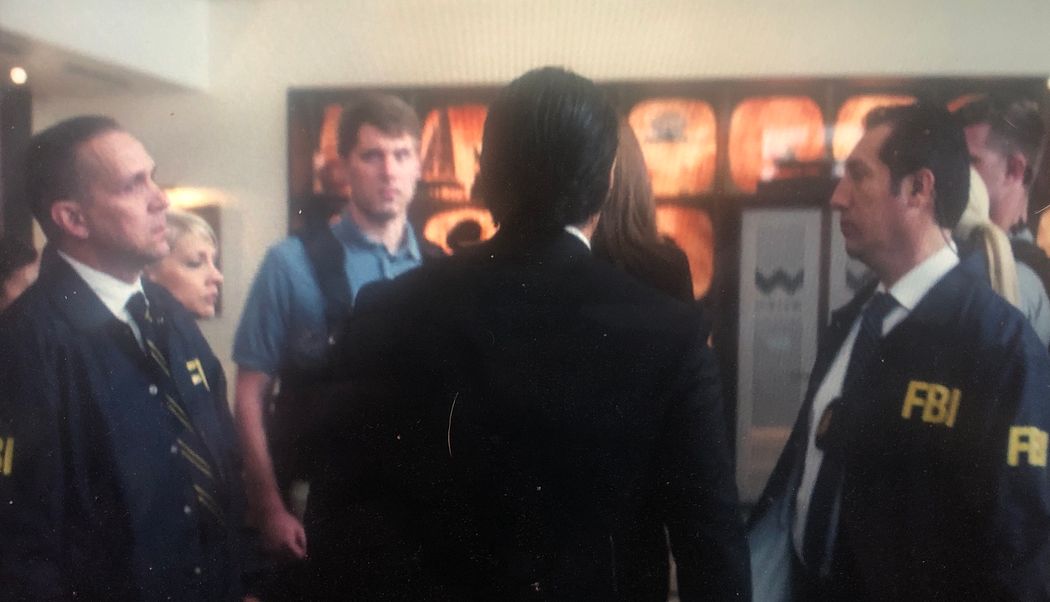

Dahlman even had the opportunity to briefly join the movie because he was on set and resembled a background actor who had an emergency on the day of filming. “The director walked over, and he’s like, ‘do you have acting experience,’” Dahlman recalled. “I was like, ‘of course I do.’” He played one of the FBI agents that raids the pharmaceutical company in the film.

James Dahlman joined the background cast of Rampage to play a federal agent for a movie scene.

Jordan Cattie

When he wasn’t teaching lab techniques or advising on set design, though, Dahlman said he spoke with the other actors on set. “[They were] asking me about science, and asking me about how CRISPR worked,” he said. “I explained how CRISPR worked to The Rock.”

Reflecting on the Time in the Limelight

About taking up the opportunity, Dahlman said “YOLO, so I’m going to burn three days, but it’s just so interesting.” For him, the opportunity to talk to the actors and see the infrastructure that created a movie were rewarding experiences. “It was really cool to see this little [beehive] of activity that goes into making a movie,” he said.

“It was a dream come true,” Lipkin said. He explained that his educational career began at Sarah Lawrence College, a liberal arts college, where he studied theater and took courses in philosophy and literature before he took a science class. “I never thought that I would have the pleasure, the honor, of coming full circle.”

Even after Contagion premiered, Lipkin stayed in contact with Burns and Soderbergh. When the COVID-19 pandemic hit in early 2020, Soderbergh reached out to Lipkin to develop plans to allow movies to be filmed safely. “Larry and I developed all the protocols for Hollywood,” Lipkin said. Later they brought on Jeffrey Shaman to help with modeling.

“As a consequence, we were able to film, and there were no problems on set,” Lipkin said. Subsequently, he helped coordinate testing and masking protocols for the Oscars and the Democratic National Convention.

For Dahlman, his movie consulting experience so far has been a one-off, but he said that he would jump at an opportunity to be a part of a future CRISPR-focused film. “It was a lot of fun,” he said.