|

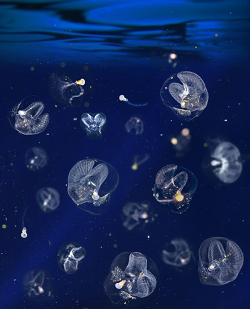

Image by Jean-Marie Bouquet and Jiri Slama, copyright Science/AAAS |

|

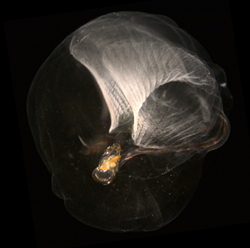

Image by Jean-Marie Bouquet and Jiri Slama, copyright Science/AAAS |

**__Related stories:__***linkurl:DNA repeats hold RNA starts;http://www.the-scientist.com/blog/display/55625/

[20th April 2009] *linkurl: Tunicate classification;http://www.the-scientist.com/2008/01/1/55/1/

[1st January 2008] *linkurl:Ascidian genome;http://www.the-scientist.com/news/20021213/01/

[13th December 2002]