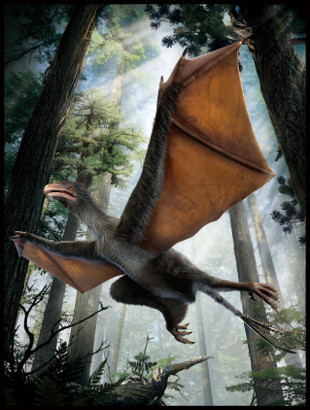

An artist's rendition of Yi qiCREDIT: DINOSTAR CO. LTDAn international team of scientists has described a curious fossil that they say belongs to a new species of dinosaur that may have had wings for flying or gliding without the benefit of well-developed feathers. Dubbed Yi qi (“strange wing” in Mandarin), the species was found in northeastern China and lived in the Jurassic Period 160 million years ago—10 million years before the appearance of the earliest known birds, like Archaeopteryx. The new dino gets its name from the slender bones that extend from its wrists. “At first we just didn’t know what the rod-like bones were,” study coauthor Corwin Sullivan, a Canadian paleontologist based at the Institute of Vertebrate Paleontology and Paleoanthropology (IVPP) in Beijing, said in a statement. “Then I was digging into the scientific literature on flying and gliding vertebrates for a totally different project, and I came across a paragraph in a textbook that said flying squirrels have a strut of cartilage attached to either the wrist or elbow to help support the flight membrane. I immediately thought, wait a minute – that sounds familiar!” Sullivan and his coauthors published the results Wednesday (April 29) in Nature.

An artist's rendition of Yi qiCREDIT: DINOSTAR CO. LTDAn international team of scientists has described a curious fossil that they say belongs to a new species of dinosaur that may have had wings for flying or gliding without the benefit of well-developed feathers. Dubbed Yi qi (“strange wing” in Mandarin), the species was found in northeastern China and lived in the Jurassic Period 160 million years ago—10 million years before the appearance of the earliest known birds, like Archaeopteryx. The new dino gets its name from the slender bones that extend from its wrists. “At first we just didn’t know what the rod-like bones were,” study coauthor Corwin Sullivan, a Canadian paleontologist based at the Institute of Vertebrate Paleontology and Paleoanthropology (IVPP) in Beijing, said in a statement. “Then I was digging into the scientific literature on flying and gliding vertebrates for a totally different project, and I came across a paragraph in a textbook that said flying squirrels have a strut of cartilage attached to either the wrist or elbow to help support the flight membrane. I immediately thought, wait a minute – that sounds familiar!” Sullivan and his coauthors published the results Wednesday (April 29) in Nature.

The new species, a member of the poorly understood scansoriopterygid group of dinosaurs, likely weighed less than 450 grams (15.9 ounces), with a skull that was a mere four centimeters (1.6 inches) long. It also had filamentous feathers, unlike the feathers of modern birds. If Yi qi indeed flew, either by flapping or gliding, it would be a dinosaur first, though ancient reptile called pterosaurs flew quite capably using a membranous wing. “No other bird or dinosaur has a wing of the same kind,” IVPP paleontologist Xu Xing said in a statement. “We don’t know if Yi qi was flapping or gliding, or both, but it definitely evolved a wing that is unique in the context of the transition from dinosaurs to birds.” The researchers ...