|

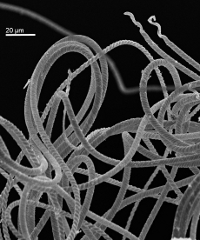

of ostracode sperm Image: Renate Matzke-Karasz |

**__Related stories:__***linkurl:Drosophila's sex peptide;http://www.the-scientist.com/article/display/21480/

[22nd July 2003]*linkurl:Sperm size matters;http://www.the-scientist.com/article/display/20846/

[8th November 2002]*linkurl:Promiscuity in Trinidad;http://www.the-scientist.com/article/display/19144/

[4th September 2000]