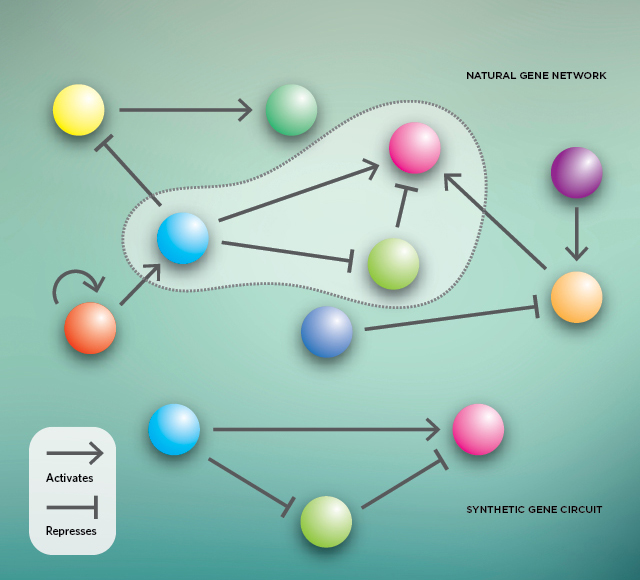

A naturally occurring gene network consists of many interacting genes that can activate or repress each other (top). But embedded within a larger network, their function can be hard to study. Synthetic biology can simplify the study of such gene interactions by engineering analogous circuits separate from the larger network (bottom).

COURTESY OF RICHARD MUSCATA number of motifs that appear in naturally occurring networks have been reconstructed in synthetic circuits. Positive autoregulation (left) occurs when a gene is activated by its own product; this results in delayed activation. (The black dotted line provides a comparison to gene activation with no autoregulation.) Conversely, negative autoregulation occurs when a gene represses its own expression (middle), allowing its rapid activation until it reaches a steady state, and then preventing overexpression. Finally, a combination of several genes can form a motif known as a feed-forward loop (right). Depending on the way the genes are connected, activating a single gene triggers the simultaneous activation and repression of another gene, causing a pulse in expression followed by a lower steady state.

COURTESY OF RICHARD MUSCATA number of motifs that appear in naturally occurring networks have been reconstructed in synthetic circuits. Positive autoregulation (left) occurs when a gene is activated by its own product; this results in delayed activation. (The black dotted line provides a comparison to gene activation with no autoregulation.) Conversely, negative autoregulation occurs when a gene represses its own expression (middle), allowing its rapid activation until it reaches a steady state, and then preventing overexpression. Finally, a combination of several genes can form a motif known as a feed-forward loop (right). Depending on the way the genes are connected, activating a single gene triggers the simultaneous activation and repression of another gene, causing a pulse in expression followed by a lower steady state.

COURTESY OF RICHARD MUSCAT

COURTESY OF RICHARD MUSCAT

Two populations of bacteria interact via signaling molecules to coordinate expression of fluorescent proteins. When using positive and negative autoregulation (top), the oscillations are robust as the two populations grow. The negative feedback loop of the repressor strain and the positive feedback loop of the activator strain thus reinforce ...