Far below the reach of sunlight in the west Pacific Ocean, fissures in the seabed spew toxic, sulfide-rich scalding hot water. These hydrothermal vents are home to a tiny, one-centimeter-long, bright yellow worm called Paralvinella hessleri, which feeds on arsenic-containing microbial mats on the ocean floor. The extreme environment protects the worm from predators, but scientists did not fully understand how the creatures themselves tolerated it.

In a study published today in PLOS Biology, researchers led by Chaolun Li, a marine ecologist at the Chinese Academy of Sciences, found that the worms fight one poison with another: They accumulate arsenic in their skin cell granules where it mixes with hydrogen sulfide likely diffused from the hydrothermal vents, forming a less harmful mineral.1 These results provide deeper clues on how marine invertebrates adapt to harsh environments.

The worm P. hessleri (yellow) inhabits hydrothermal vents deep underwater.

Wang H, et al., 2025, PLOS Biology, CC-BY 4.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/)

“This was my first deep-sea expedition,” said study coauthor Hao Wang, a deep-sea biologist at the Chinese Academy of Sciences, in a press release. “I was stunned by what I saw on the ROV monitor—the bright yellow Paralvinella hessleri worms were unlike anything I had ever seen, standing out vividly against the white biofilm and dark hydrothermal vent landscape.”

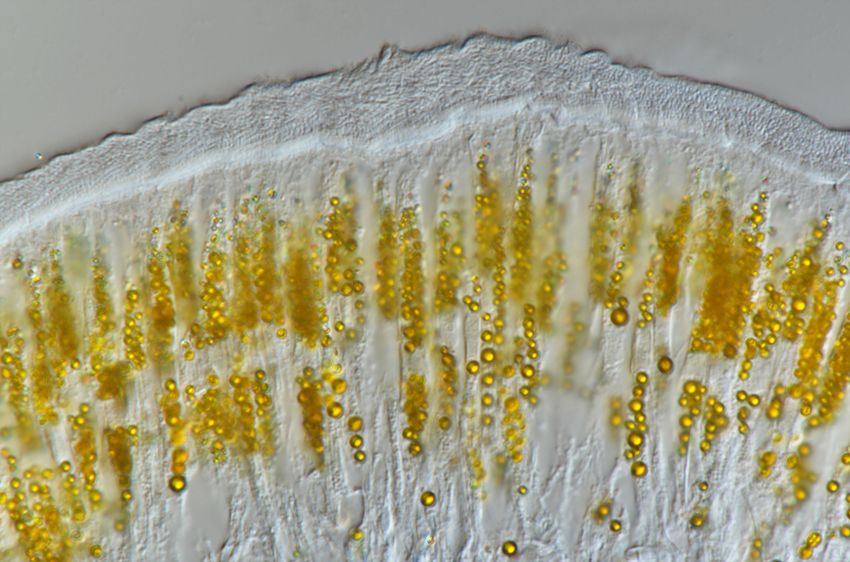

Unlike this vibrant worm, most other deep-sea denizens that live in total darkness exhibit sober colors. The researchers dissected the worm and found that they contained yellow granules in all the cells that were in direct contact with seawater.

Elemental analyses using electron microscopy indicated that the granules contained arsenic and sulfur, which reacted to produce a yellow-colored mineral called orpiment.2 Spectrometry analysis confirmed that the granules were mostly composed of this mineral.

Further investigation revealed that lipid bilayer membranes enveloped the granules. Other researchers had previously reported that a bacterium belonging to Entotheonella species contained similar intracellular vacuoles to mineralize and detoxify arsenic.3 Drawing on this, Li and his team hypothesized that the membrane surrounding the granules helps transport arsenic into the granules where it mineralizes to form orpiment.

Li and his team sectioned the P. hessleri tissue and observed yellow-colored granules.

Wang H, et al., 2025, PLOS Biology, CC-BY 4.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/)

By studying the worm’s proteome, the researchers found that the membranes contained a transporter protein that could potentially shuttle arsenic. It also revealed that the granule-containing vacuoles carried hemoglobins which help diffuse gases like hydrogen sulfide that are emitted by hydrothermal vents.

Based on these data, Li and his team propose that hydrogen sulfide diffuses into the skin cells of P. hessleri and forms complexes with hemoglobin, which transports it into vacuoles. Meanwhile, membrane transporters ferry bioaccumulated arsenic into the vacuoles, where it reacts with the sulfide and deposits insoluble nontoxic orpiment minerals.

According to the researchers, this “fighting poison with poison” model offers insights on the evolutionary adaptations that regulate how marine invertebrates deal with toxic elements in their environment. However, they noted that their results do not completely explain the arsenic transport mechanism, which they hope will get easier to study when scientists solve the challenges associated with culturing the worms in lab.

- Wang H, et al. A deep-sea hydrothermal vent worm detoxifies arsenic and sulfur by intracellular biomineralization of orpiment (As2S3). PLoS Biol. 2025;23(8):e3003291.

- Gliozzo E, Burgio L. Pigments—Arsenic-based yellows and reds. Archaeol Anthropol Sci. 2022;14(1);4.

- Keren R, et al. Sponge-associated bacteria mineralize arsenic and barium on intracellular vesicles. Nat Commun. 2017;8:14393.