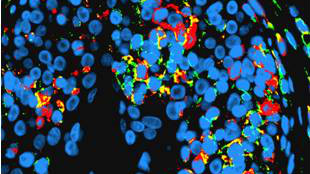

A mixture of recipient and donor immune cells during rejectionCOURTESY OF BRIGHAM AND WOMEN'S HOSPITALIn recent years, pioneering surgeons have been transplanting faces, giving newfound features, facial mobility, and other benefits to patients whose own faces have been badly disfigured. Serial skin biopsies from five face transplant recipients at Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston are now shedding light on the dynamics of rejection, a phenomenon in which the transplant recipient’s immune system recognizes the donor tissue as foreign, according to a paper published today (January 17) in Modern Pathology. Contrary to previous assumptions, it appears that the transplant recipient’s T cells are not the only immune cells active at rejection sites—the Boston team found that T cells from the donor can be found there, too.

A mixture of recipient and donor immune cells during rejectionCOURTESY OF BRIGHAM AND WOMEN'S HOSPITALIn recent years, pioneering surgeons have been transplanting faces, giving newfound features, facial mobility, and other benefits to patients whose own faces have been badly disfigured. Serial skin biopsies from five face transplant recipients at Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston are now shedding light on the dynamics of rejection, a phenomenon in which the transplant recipient’s immune system recognizes the donor tissue as foreign, according to a paper published today (January 17) in Modern Pathology. Contrary to previous assumptions, it appears that the transplant recipient’s T cells are not the only immune cells active at rejection sites—the Boston team found that T cells from the donor can be found there, too.

“I think the most fascinating possibility is that the passenger resident immune cells . . . might actually be mustering a counterattack against the recipient immune cells that are trying to reject the face,” said study coauthor George Murphy, a skin pathologist at Brigham and Women’s Hospital. A more thorough understanding of the role of donor T cells in controlling rejection could influence medical decisions on how to treat rejection. If it turns out that donor immune cells are indeed fighting off rejection, “it will rewrite in some ways our understanding of the complexity of transplant rejection,” Murphy said.

But Linda Cendales, a hand transplant surgeon at Emory University in Atlanta who was not involved in the study, noted that staining of donor T cells ...