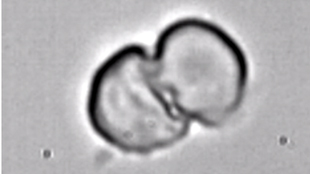

A pair of MIN6 cellsADAM HIGGINS AND JENS KARLSSONCryopreservation of individual cells—most often germ cells, like sperm or eggs—can be accomplished with relatively little damage to the specimens, but freezing tissues or organs is significantly more challenging. One reason for the difficulty is that connected cells are prone to intracellular ice formation (IIF), which is usually lethal. It had been proposed that the gap junctions between cells in a tissue allow IIF to spread, but now researchers show that it is actually defects in the tight junctions that permit ice to penetrate the cells in tissues. The work is published today in the Biophysical Journal.

A pair of MIN6 cellsADAM HIGGINS AND JENS KARLSSONCryopreservation of individual cells—most often germ cells, like sperm or eggs—can be accomplished with relatively little damage to the specimens, but freezing tissues or organs is significantly more challenging. One reason for the difficulty is that connected cells are prone to intracellular ice formation (IIF), which is usually lethal. It had been proposed that the gap junctions between cells in a tissue allow IIF to spread, but now researchers show that it is actually defects in the tight junctions that permit ice to penetrate the cells in tissues. The work is published today in the Biophysical Journal.

The paper “has important implications in explaining ice formation and the ensuing injury in tissues, a poorly understood phenomenon in cryobiology and regenerative medicine research,” John Bischof, a professor of mechanical engineering at the University of Minnesota, who was not involved in the work, wrote in an e-mail.

For this investigation, study coauthors Jens Karlsson, an associate professor of mechanical engineering at Villanova University in Pennsylvania, and Adam Higgins, an assistant professor in the School of Chemical, Biological, and Environmental Engineering at Oregon State University, used adherent mouse MIN6 insulinoma cells, which stick together in pairs. They used MIN6 cell lines with normal gap junctions and those that were treated with antisense RNA to the gap junction protein connexin-36. The researchers recorded high-speed cryomicroscopy videos ...