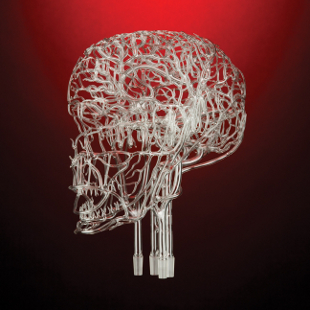

Courtesy of Farlow’s Scientific GlassblowingAt first glance it looks like an ornate crystal sculpture—the sort of priceless ancient artefact that Indiana Jones might risk life and limb to save for posterity. Get a little closer, though, and this intricate arrangement of glass tubes reveals itself as an accurate replica of the brain’s labyrinthine vascular system. In fact, it’s part of a range of anatomically precise models used by cardiologists for training, and by medical device manufacturers to test their latest life-saving catheters and valves.

Courtesy of Farlow’s Scientific GlassblowingAt first glance it looks like an ornate crystal sculpture—the sort of priceless ancient artefact that Indiana Jones might risk life and limb to save for posterity. Get a little closer, though, and this intricate arrangement of glass tubes reveals itself as an accurate replica of the brain’s labyrinthine vascular system. In fact, it’s part of a range of anatomically precise models used by cardiologists for training, and by medical device manufacturers to test their latest life-saving catheters and valves.

Every one is made by hand (and mouth) at Farlow’s Scientific Glassblowing (FSG), a family-run company in Grass Valley, California, where the age-old art of glassblowing meets the rigorous requirements of modern medical science.

There, skilled glassblowers painstakingly shape and fuse each individual artery, vein and capillary from borosilicate glass, adding connectors at the exposed ends so their clients can hook the models up to pumping devices to simulate blood flow conditions. They create everything from aneurysms to atriums. They even craft an intricate full-body model, described as “an always willing patient,” that features all major arteries leading from a four-chambered heart.

“Most of our products are custom made to specification, and they take a while,” says Wade Martindale, manager of the vascular models division ...