© ANDRZEJ WOJCICKI/SCIENCE PHOTO LIBRARYPlant pathologist Jean Ristaino hunts down crop-threatening diseases all over the world. Last year, in the span of two months, she visited India, Uganda, and Taiwan to help colleagues track the fungus Phytophthora infestans, which infects tomatoes and potatoes and caused numerous famines in 19th-century Europe. Ristaino tracks the pathogen’s modern march using farmers’ online reports of outbreaks of the disease, called late blight; then she travels to those locations to collect fungal samples. In her lab at North Carolina State University in Raleigh, Ristaino’s team genotypes fungi from these farms to trace their origins and monitor how P. infestans’s genome is changing in response to fungicide use and how it’s subverting immune strategies the host plants use to defend themselves.

© ANDRZEJ WOJCICKI/SCIENCE PHOTO LIBRARYPlant pathologist Jean Ristaino hunts down crop-threatening diseases all over the world. Last year, in the span of two months, she visited India, Uganda, and Taiwan to help colleagues track the fungus Phytophthora infestans, which infects tomatoes and potatoes and caused numerous famines in 19th-century Europe. Ristaino tracks the pathogen’s modern march using farmers’ online reports of outbreaks of the disease, called late blight; then she travels to those locations to collect fungal samples. In her lab at North Carolina State University in Raleigh, Ristaino’s team genotypes fungi from these farms to trace their origins and monitor how P. infestans’s genome is changing in response to fungicide use and how it’s subverting immune strategies the host plants use to defend themselves.

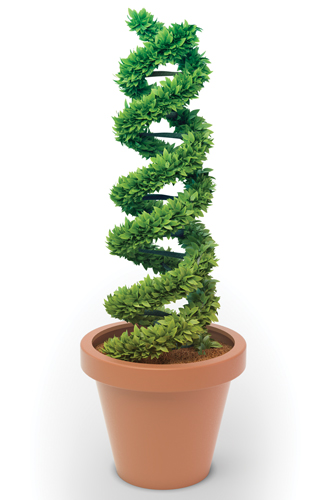

Just like animals, plants have to fight off pathogens looking for an unsuspecting cell to prey on. Unlike animals, however, plants don’t have mobile immune cells patrolling for invaders. “Every cell has to be an immune-competent cell,” says Jeff Dangl, who studies plant-microbe interactions at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

Decades of work on model plants such as Arabidopsis thaliana have revealed robust cellular immune pathways. First, plasma membrane receptors recognize bits of pathogen and kick-start signaling cascades that alter hormone levels and immune-gene expression. This triggers the cell to reinforce its wall and to release reactive oxygen species and nonspecific antimicrobial compounds to fight the invaders. These responses can also be ramped up and prolonged by a second immune pathway, which ...