For most people, a day’s meals offer a variety of food with different levels of nutrition. Breakfast could be a meager bowl of cereal loaded with artificial sweeteners, while lunch may bring with it a hearty salad, providing a healthy balance of macronutrients. The gut can detect these differences accurately and accordingly modify intestinal behaviors.1 Studies done in rodents have shown that a nutritious meal promotes mixing, digestion, and absorption of food, while non-caloric sweeteners or diarrhea-inducing toxins trigger propulsive contractions to quickly eliminate the substances from the gut.2,3 However, how the gut’s sensory neurons detect and differentiate intestinal chemicals is shrouded in mystery.

“There’s this assumption that the central nervous system is more important and controls everything, while the enteric neurons are a kind of housekeeping system,” said Ivan de Araujo, a neuroscientist at the Max Planck Institute for Biological Cybernetics.

Now, in a recent study published in Nature, researchers identified subsets of enteric sensory neurons in mice that rely on the neurotransmitter serotonin to respond to different nutrients.4 These findings lay the foundation for understanding how the intestine monitors its contents, shaping its functional output as well as the animal’s behavior like cravings and aversions, in addition to the control mediated via the central nervous system.

Pieter Vanden Berghe is a bioengineer at KU Leuven who studies the development and functionality of enteric neurons embedded in the gut.

Pieter VANDEN Berghe

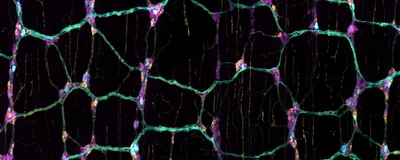

The enteric nervous system comprises a plethora of neuron types organized into two regions: the submucosal plexus (SMP) that regulates intestinal secretions and the myenteric plexus (MP) that controls motility.5 To uncover the neuronal dynamics of nutrient sensing, Pieter Vanden Berghe, a bioengineer at KU Leuven, teamed up with Candice Fung, a neuroscientist and postdoctoral researcher in his lab. First, they mapped the anatomy of the enteric neurons within the villi—intestinal finger-like projections that absorb nutrients. They dissected out a section of mouse intestines and injected a neuronal dye into the tip of a single villus, which led to neurons close to the surface lighting up. They observed that a generic neuronal stimulant activated neurons in both SMP and MP.

But the real question was whether the neurons responded differently to distinct nutrients. So, Vanden Berghe and his team analyzed the activity of the neurons as they applied three nutrient solutions to the intestinal mucosal section: glucose (sugar), L-phenylalanine (amino acid), and acetate (short-chain fatty acid). The three solutions each activated roughly 20 percent of SMP neurons. In the MP, each nutrient triggered responses in a unique subset of neurons, with sweet-sensing cell populations being the most abundant.

Candice Fung is postdoctoral researcher in Pieter Vanden Berghe’s lab at KU Leuven, where she studies how the gut detects and processes information.

Candice Fung

Next, Vanden Berghe and Fung wanted to identify neurotransmitters that mediate nutrient signals to the enteric neurons via the mucosal cells. They focused on the molecules implicated in nutrient signaling, such as serotonin, ATP, and GLP-1, and injected them into the villi. Microscopy revealed that serotonin triggered responses in the largest fraction of MP neurons. To link this back to intestinal sensing, the team chemically activated all gut sensory neurons and observed release of serotonin from the mucosal cells.

This did not surprise de Araujo, who noted that serotonin plays major roles in the gut, that range from regulating motility, controlling water absorption, all the way to modulating responses to infections.

A deeper analysis of the spatial organization of the information flow revealed that some nutrients activated MP neurons first, which is further away from the intestinal lumen, which then talked to SMP neurons. “This was very surprising and exciting,” Vanden Berghe said. According to de Araujo, this connection between nutrients and the MP indicates local modulation of gut motility.

Until this point, the team used a dissected segment of mouse intestine to perform experiments, which did not accurately mimic the tissue physiology. However, examining cells in an intact intestine is challenging. “It's very difficult to study enteric neurons because they are deep into gut tissue. It's very hard to record their activity in an animal,” de Araujo said.

This is where Vanden Berghe applied his bioengineering expertise. “My thing is to develop technology to see what we could not see yesterday,” he said. So, the team designed a system to examine the mouse enteric nervous system in vivo. They exposed a segment of the intestine while it was still attached to a live animal, applied acetate solution to the mucosa, and tracked neuron activation in the MP. Consistent with their previous observations, the nutrient activated only 15 percent of MP neurons.

“Nobody has really looked into a living mouse, injected nutrients, with the intestine still physiologically so intact and so healthy as [Candice] did,” Vanden Berghe said.

According to the researchers, these findings open avenues to explore how nutrients change metabolism and impact food-related behaviors like cravings. Going forward, Fung and Vanden Berghe are excited to focus on one such path and understand how chemicals in ultra-processed foods alter an individual’s nutrient perception.

- Neunlist M, Schemann M. Nutrient-induced changes in the phenotype and function of the enteric nervous system. J Physiol. 2014;592(14):2959-2965.

- Schemann M, Ehrlein HJ. Postprandial patterns of canine jejunal motility and transit of luminal content. Gastroenterology. 1986;90(4):991-1000.

- Nocerino A et al. Cholera toxin-induced small intestinal secretion has a secretory effect on the colon of the rat. Gastroenterology. 1995;108(1):34-39.

- Fung C et al. Nutrients activate distinct patterns of small-intestinal enteric neurons. Nature. 2025:1-9.

- Fung C, Berghe PV. Functional circuits and signal processing in the enteric nervous system. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2020;77(22):4505-4522.