Writing a good abstract is an important skill for scientists to have and develop.

iStock, Dakota Oldeman

The title and the abstract form the gateway to a study, and a well-defined combination rolls out the red carpet for the audience. The ability to write a good abstract is therefore an important skill, and one that scientists go out of their way to develop. However, authors are often tempted to try and fit everything into their abstracts despite character and word limits. This creates crowded, overwhelming, and meandering works that turn the audience away. Writers should remember that a study is best communicated as a narrative—a story—and a good abstract should provide a preview of that story rather than a compressed version of the manuscript as a whole.

Identifying and Prioritizing Key Information

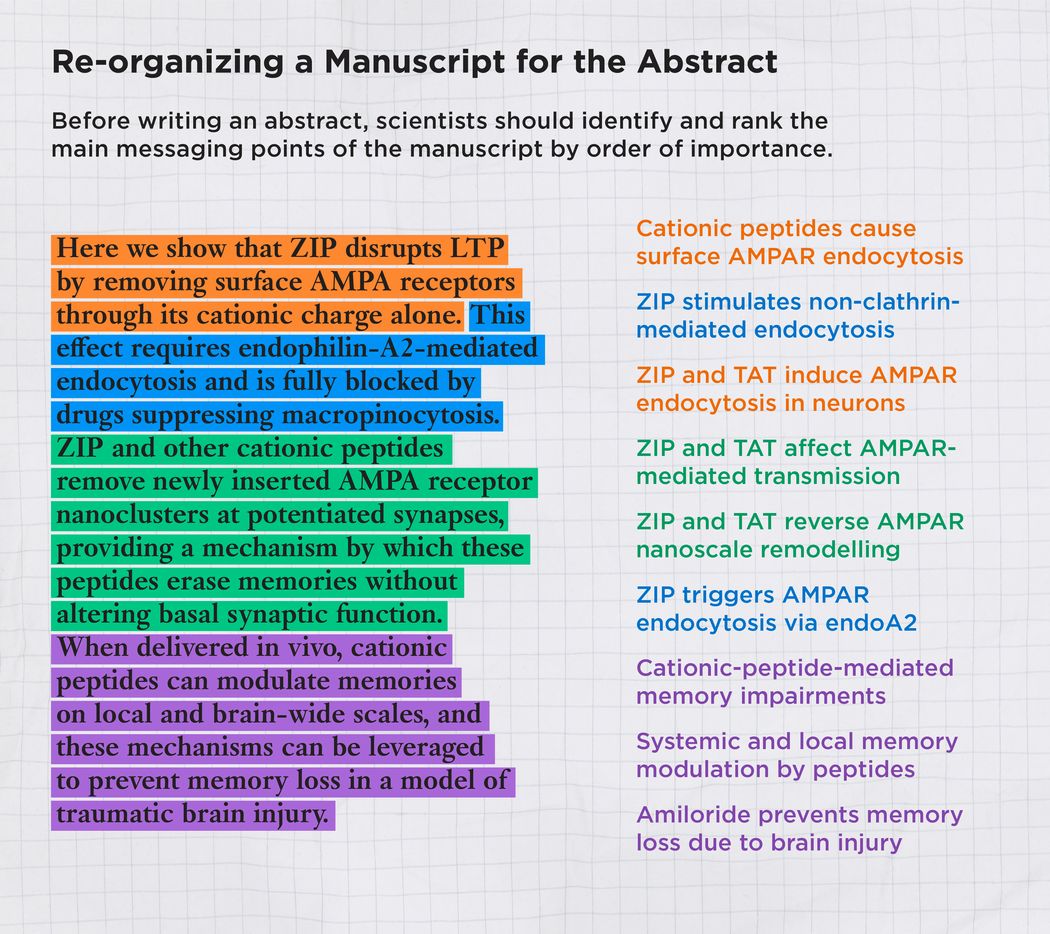

Before writing a manuscript, authors should outline and organize their concepts, data, interpretations, and conclusions to form a cohesive narrative. They should do the same thing before writing an abstract—with one key additional consideration. Because abstracts come with much more stringent length constraints, scientists will often have to leave some information on the cutting room floor. As such, the best thing to do is to identify and rank the main messaging points of the manuscript by order of importance. For example, in this article in Nature, neurobiologist Kevin Beier and his research team at the University of California, Irvine organized their findings into nine different sections. However, in the abstract, they broadly summarized these nine sections into four sentences, corresponding with sections 1 and 3, 2, 4-6, and 7-9, respectively.1

The Scientist Team

Through this arrangement, the authors have identified “Cationic peptides cause surface AMPAR endocytosis” and “ZIP and TAT induce AMPAR endocytosis in neurons” as the primary findings, and then positioned “ZIP stimulates non-clathrin-mediated endocytosis” and “ZIP triggers AMPAR endocytosis via endoA2” as secondary findings that provide additional context for the primary findings. Following this, they go on to provide details in the third sentence about how the primary findings work, and conclude in the fourth sentence with information on phenotypic relevance.1 This process not only helped Beier and his team better organize their findings, but it also established a narrative within their abstract.

Building the Narrative in an Abstract

Just as with complete manuscripts, narratives are key to a successful abstract. Narratives in abstracts and manuscripts comprise the same elements: some scientific background information, the question being investigated, the study hypothesis and rationale, the methodology, the results, the data interpretation, and the study implications. However, because the abstract comes with more rigid space limitations, most abstracts cannot contain all of the aforementioned elements, meaning that researchers have to pick and choose.

This can cause scientists to overemphasize their results at the expense of the other components of a good narrative. But results need to be supported by context to be effective. As such, authors need to take care to not include data points that are not linked to either the rationale, the methodology, or the already introduced data points. Authors should also likewise not introduce background facts that are not related to the data, nor data that is not interpreted or does not impact the conclusion.

Another way to streamline the results and present data within a framework of a narrative is to focus on relationships rather than numbers. Many abstracts present information in a “group A showed a value of 12, while group B showed a value of 16” template. Not only is this lacking context, but it is also wordy and clunky. Instead, they should focus on relationships, such as “group B showed a higher value than group A,” and incorporate values where appropriate.

For example, environmental scientist Xavier Basurto from Duke University and his colleagues used numbers to illustrate and emphasize the importance of small-scale fisheries (SSF) in their article published in Nature, stating, “Through a collaborative and multidimensional data-driven approach, we have estimated that SSF provide at least 40% (37.3 million tonnes) of global fisheries catches and 2.3 billion people with, on average, 20% of their dietary intake across six key micronutrients essential for human health.”2

Finally, one way to smoothly squeeze more information into an abstract is to combine the methodology with the results, such as what neurobiologist Ryan Hibbs and his team from the University of California, San Diego did in their Nature article when they state, “Using cryo-electron microscopy, we defined a set of 12 native subunit assemblies and their 3D structures. We address inconsistencies between previous native and recombinant approaches, and reveal details of previously undefined subunit interfaces.”3

Managing Word and Character Count

Space constraints play a large role in abstract construction. However, rather than worrying about specific word and character counts at the beginning, it is much more effective to trim around the edges of an already constructed abstract. It is always easier to remove rather than to add.

Scientists can take several steps to make the editing and cutting process easier. First, they should keep their sentences short and limit each sentence to one or two clauses. This not only helps readability, but it also means that editing one clause will not have a domino effect on three or four other clauses. Second, they should limit the use of jargon because these terms need to be defined and explained for the audience, which takes up space. Third, writers should take care to keep their descriptions and expositions concise. Scientists tend to want to present all the information at their disposal, but the audience understands that the abstract is not the place for that.

Finally, authors can reduce word and character counts by tweaking syntax and word selection. For example, active voice is more succinct than passive voice. “The cells were strongly influenced by the treatment” contains eight words and 51 characters, whereas “The treatment strongly influenced the cells” is made up of six words and 43 characters.

Using shorter words can help shave characters: writers can try “use” instead of “utilize” and “probe” or “study” instead of “investigate.” Also, they can try to identify and avoid redundant phrases. For example, the sentence “When measured, it was found that cell growth increased two-fold when stimulated” could simply be written as “Stimulated cells grew at twice the rate” or “Stimulation increased cell growth two-fold.” These adjustments seem small, but they add up. Five or so fixes along these lines could provide an additional ten or fifteen words to play with.

Each Abstract Is Different

Each abstract will be uniquely shaped by what they are trying to summarize—whether it is a manuscript, presentation, poster, or something else. They will be impacted by the specific space restrictions, which can range anywhere from 150 to 350 words. They will be affected by how much information the author has on hand, and how much of that they want to publicly present. There is no one-size-fits-all solution to abstract writing. However, recognizing the general guidelines presented here will give scientists an idea of what is a good and what is a bad abstract, providing them a solid foundation from which they can adapt as the situation requires.

Looking for more information on scientific writing? Check out The Scientist’s TS SciComm section. Looking for some help putting together a manuscript, a figure, a poster, or anything else? The Scientist’s Scientific Services may have the professional help that you need.

- Stokes EG, et al. Cationic peptides cause memory loss through endophilin-mediated endocytosis. Nature. 2025.

- Basurto X, et al. Illuminating the multidimensional contributions of small-scale fisheries. Nature. 2025;637:875–884.

- Zhou J, et al. Resolving native GABAA receptor structures from the human brain. Nature. 2025.