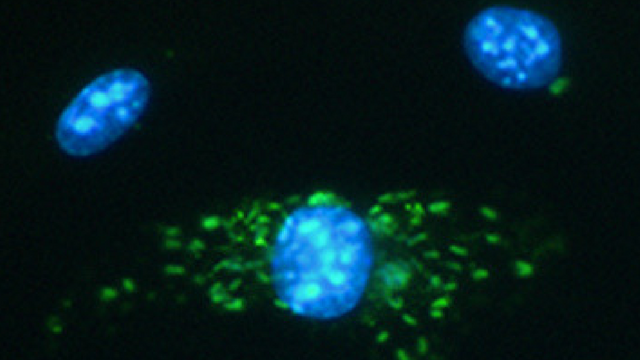

Mouse macrophages (blue) and Legionella pneumophila serogroup 6 (green). Twenty hours after 1-2 bacteria were introduced, the bottom macrophage became infected with replicating bacteria.

Mouse macrophages (blue) and Legionella pneumophila serogroup 6 (green). Twenty hours after 1-2 bacteria were introduced, the bottom macrophage became infected with replicating bacteria.

BRENDA BYRNE, UNIVERSITY OF MICHIGAN MEDICAL SCHOOL

During Flint’s contaminated water crisis in recent years, caused by a switch in water supply that triggered a swell of lead poisonings, the city simultaneously experienced outbreaks of Legionnaires’ disease that, according to the Detroit Free Press, killed 12 people and made 91 others sick. At the annual American Society for Microbiology (ASM) meeting in New Orleans this week (June 1-5), scientists report evidence that the pathogenic bacteria responsible for the disease are present in residents’ water, although they cannot confirm from the data yet if people’s taps are to blame for the infections.

Approximately 88 percent of the bacterial strains detected are difficult to diagnose in people due to a lack of diagnostic tests. Legionnaires’ disease is known as an atypical pneumonia that infects the lungs after inhaling contaminated water droplets, according to Michele Swanson, a microbiologist at the University of Michigan Medical School who is ASM’s incoming president-elect. As an opportunistic pathogen, it targets immunocompromised people and the elderly.

Experts suspect that Flint’s corrosive water supply pipes ...