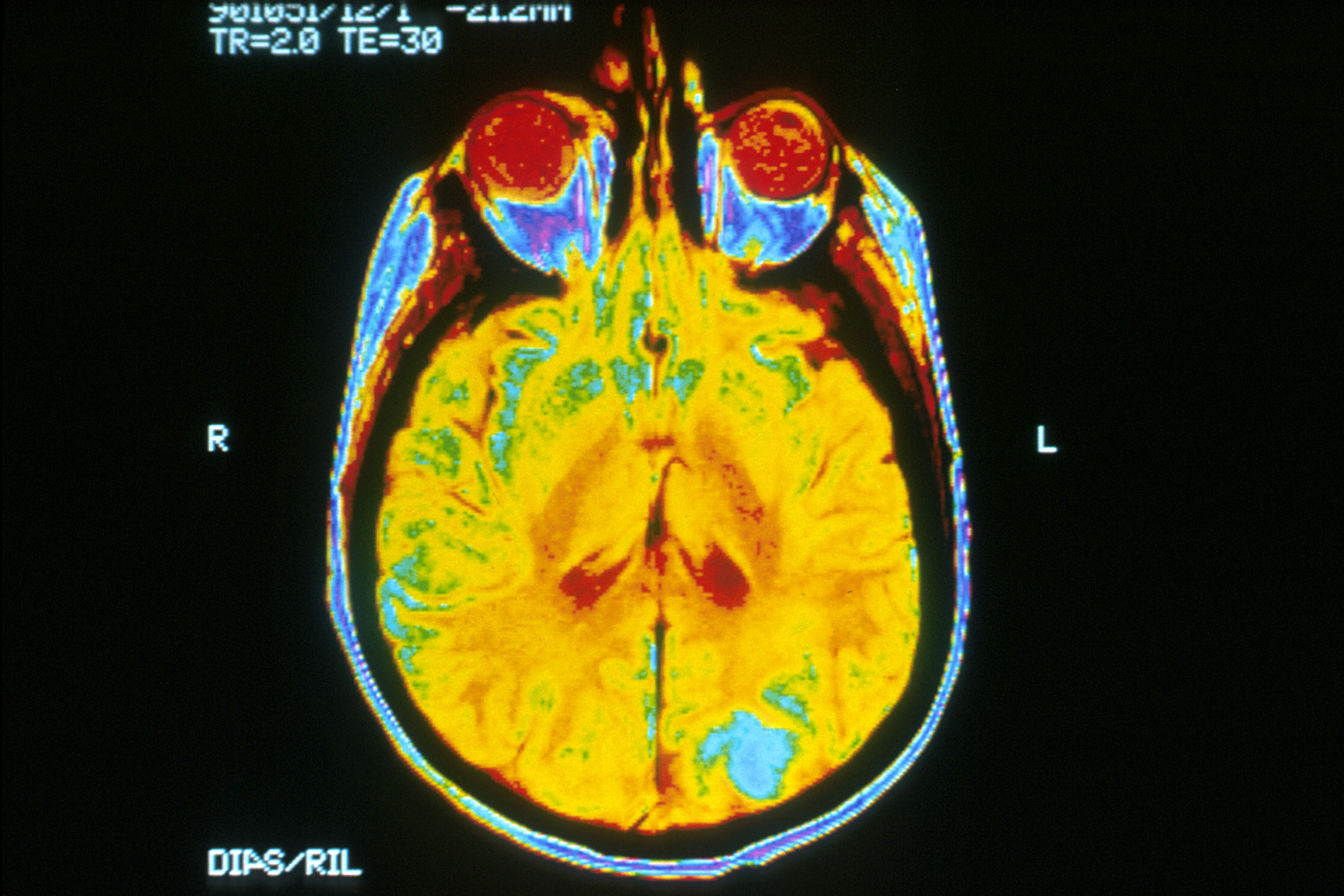

WIKIMEDIA, LEON KAUFMANOne season of high school football may be all it takes to cause noticeable changes in white matter and brainwave formation, according to a small study of 24 student athletes, which has not yet been peer-reviewed and was presented at the annual meeting (November 28) of the Radiological Society of America in Chicago. Despite no evidence of clinical concussion in any of the players examined, the study revealed a correlation between changes in brain health and players who took the most hits on the field.

WIKIMEDIA, LEON KAUFMANOne season of high school football may be all it takes to cause noticeable changes in white matter and brainwave formation, according to a small study of 24 student athletes, which has not yet been peer-reviewed and was presented at the annual meeting (November 28) of the Radiological Society of America in Chicago. Despite no evidence of clinical concussion in any of the players examined, the study revealed a correlation between changes in brain health and players who took the most hits on the field.

“We know that some professional football players suffer from a serious condition called chronic traumatic encephalopathy, or CTE,” coauthor Elizabeth Moody Davenport, a postdoc at UT Southwestern Medical Center in Dallas, said in a press release. “We are attempting to find out when and how that process starts, so that we can keep sports a healthy activity for millions of children and adolescents.”

Davenport and colleagues first scanned each player’s brain before the season started, via MRI scans of white matter and MEG scans of the functional magnetic fields produced by the athletes’ brain waves. The researchers then outfitted each player’s helmet with six accelerometers that gathered specific data about the impacts sustained. After one season of play, they repeated the brain scans.

Direct, frontal ...