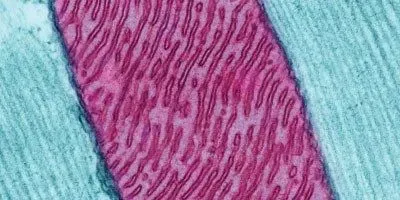

© THOMAS DEERINCK, NATIONAL CENTER FOR MICROSCOPY AND IMAGING RESEARCHBillions of years ago, one cell—the ancestral cell of modern eukaryotes—engulfed another, a microbe that gave rise to today’s mitochondria. Over evolutionary history, the relationship between our cells and these squatters has become a close one; mitochondria provide us with energy and enjoy protection from the outside environment in return. As a result of this interdependence, our mitochondria, which once possessed their own complete genome, have lost most of their genes: while the microbe that was engulfed so many years ago is estimated to have contained thousands of genes, humans have just 13 remaining protein-coding genes in their mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA).

© THOMAS DEERINCK, NATIONAL CENTER FOR MICROSCOPY AND IMAGING RESEARCHBillions of years ago, one cell—the ancestral cell of modern eukaryotes—engulfed another, a microbe that gave rise to today’s mitochondria. Over evolutionary history, the relationship between our cells and these squatters has become a close one; mitochondria provide us with energy and enjoy protection from the outside environment in return. As a result of this interdependence, our mitochondria, which once possessed their own complete genome, have lost most of their genes: while the microbe that was engulfed so many years ago is estimated to have contained thousands of genes, humans have just 13 remaining protein-coding genes in their mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA).

Some mitochondrial genes have disappeared completely; others have been transferred to our cells’ nuclei for safekeeping, away from the chemically harsh environment of the mitochondrion. This is akin to storing books in a nice, dry, central library, instead of a leaky shed where they could get damaged. In humans, damage to mitochondrial genes can result in devastating genetic diseases, so why keep any books at all in the leaky shed?

Researchers have proposed diverse hypotheses to explain mitochondrial gene retention. Perhaps the products of some genes are hard to introduce into the mitochondrion once they’ve been made elsewhere. (Mitochondria have their own ribosomes and are capable of translating their retained genes in-house.) Or perhaps keeping some mitochondrial genes allows the cell to control each organelle ...