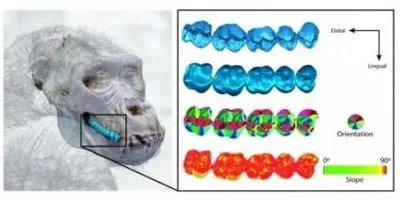

A map of a western gorilla's (Gorilla gorilla) back teeth, made using a new method that incorporates elements of GIS.IMAGE: SILVIA PINEDA-MUNOZ/SMITHSONIANThe challenge of teasing apart the diets of extinct animals may have just gotten a bit easier, thanks to a new approach to mapping dentition in living species. The technique, which was published last week (November 21) in Methods in Ecology and Evolution, uses 3D scans of teeth to create something akin to a topographic map. Then an algorithm compares maps of living and extinct species to infer what the diet of the latter might have been and how tooth morphology may have changed through evolutionary time.

A map of a western gorilla's (Gorilla gorilla) back teeth, made using a new method that incorporates elements of GIS.IMAGE: SILVIA PINEDA-MUNOZ/SMITHSONIANThe challenge of teasing apart the diets of extinct animals may have just gotten a bit easier, thanks to a new approach to mapping dentition in living species. The technique, which was published last week (November 21) in Methods in Ecology and Evolution, uses 3D scans of teeth to create something akin to a topographic map. Then an algorithm compares maps of living and extinct species to infer what the diet of the latter might have been and how tooth morphology may have changed through evolutionary time.

“The new method gives researchers a way to measure changes that arose as animals adapted to environments altered by mass extinctions or major climate shifts,” Smithsonian paleontologist and coauthor Sílvia Pineda-Munoz said in a statement. “By using shape algorithms to examine teeth before and after these perturbations, we can understand the morphological adaptations that happen when there is an [environmental] change.”

The backbone of the technique is a database of dentition maps, compiled by Pineda-Munoz when she was a graduate student. The database illustrates the dentition of 134 extant mammal species, which fit into eight different dietary categories. “Those categories give detailed information about an animal’s primary food source, including plants, meat, fruits, grains, insects, fungus or tree saps, with an additional ‘generalist’ diet category,” ...