© DUSAN PETRICIC

© DUSAN PETRICIC

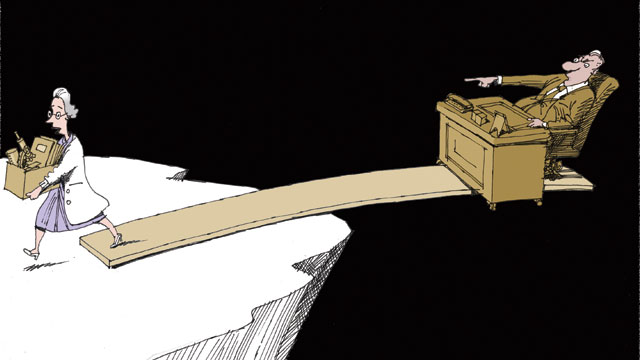

Have you ever been laid off? It happened to me for the first time this February, along with a considerable number of my colleagues, two years after my longtime employer—a truly innovative and forward-thinking midsize pharmaceutical company—was purchased by a larger pharma company. As is customary in such situations, a security guard escorted me to my office, where I was instructed to pack my things into two cardboard boxes. It was an altogether surreal experience, one that some of you may know all too well. Layoffs have become an unfortunately familiar part of life in the pharmaceutical industry, and R&D is always low-hanging fruit in such situations, as we do not make money for the company in the short term. Scientists continue to be let ...