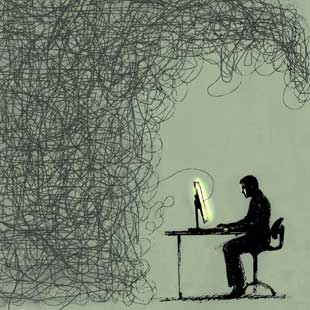

© GARY WATERS/IKON IMAGES/CORBISAs recently as five years ago, nearly all my genetics data could fit on my personal computer and could be analyzed using basic spreadsheet software. Today, my data require sophisticated analysis tools and larger storage solutions, and I am not alone. Scientists across nearly every field—from genetics to neuroscience, physics to ecology—are generating unprecedented volumes of data at speeds that would have seemed like science fiction just a few years ago. For the first time in history, researchers routinely gather more information than they can analyze in a meaningful way. As a result, science is now data-rich but discovery-poor.

© GARY WATERS/IKON IMAGES/CORBISAs recently as five years ago, nearly all my genetics data could fit on my personal computer and could be analyzed using basic spreadsheet software. Today, my data require sophisticated analysis tools and larger storage solutions, and I am not alone. Scientists across nearly every field—from genetics to neuroscience, physics to ecology—are generating unprecedented volumes of data at speeds that would have seemed like science fiction just a few years ago. For the first time in history, researchers routinely gather more information than they can analyze in a meaningful way. As a result, science is now data-rich but discovery-poor.

The solution to this modern paradox lies in developing technologies to extract meaning from all this information. But new technologies are not sufficient; researchers must also know which technologies and methods are best equipped to address the important questions for their area of study. There simply aren’t enough academic researchers who are capable of harnessing their data deluge.

How can we attract and train the experts needed to transform data into discovery across many scientific fields? This is a problem my colleague Chris Mentzel, program director of the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation’s Data-Driven Discovery Initiative, and I have been thinking about for several years. One of the challenges facing scientific progress is that career advancement has traditionally been fueled by specialization, individual discovery, and ...