To fight cancer, the immune system mobilizes all its forces.1 Innate immune cells, including macrophages, neutrophils, and monocytes, are the first recruits: They recognize cancer cells and call in reinforcements. Adaptive immune cells like cytotoxic T lymphocytes (CTLs) arrive at the scene next and begin to release cytokines. However, this attack does not last forever. The tumor environment exhausts T cells, impeding their ability to sustain an attack on cancer cells.2 This exhaustion reduces the effectiveness of immunotherapies that rely on these cells. To counter this, researchers have been trying to uncover the molecular basis of CTL exhaustion.

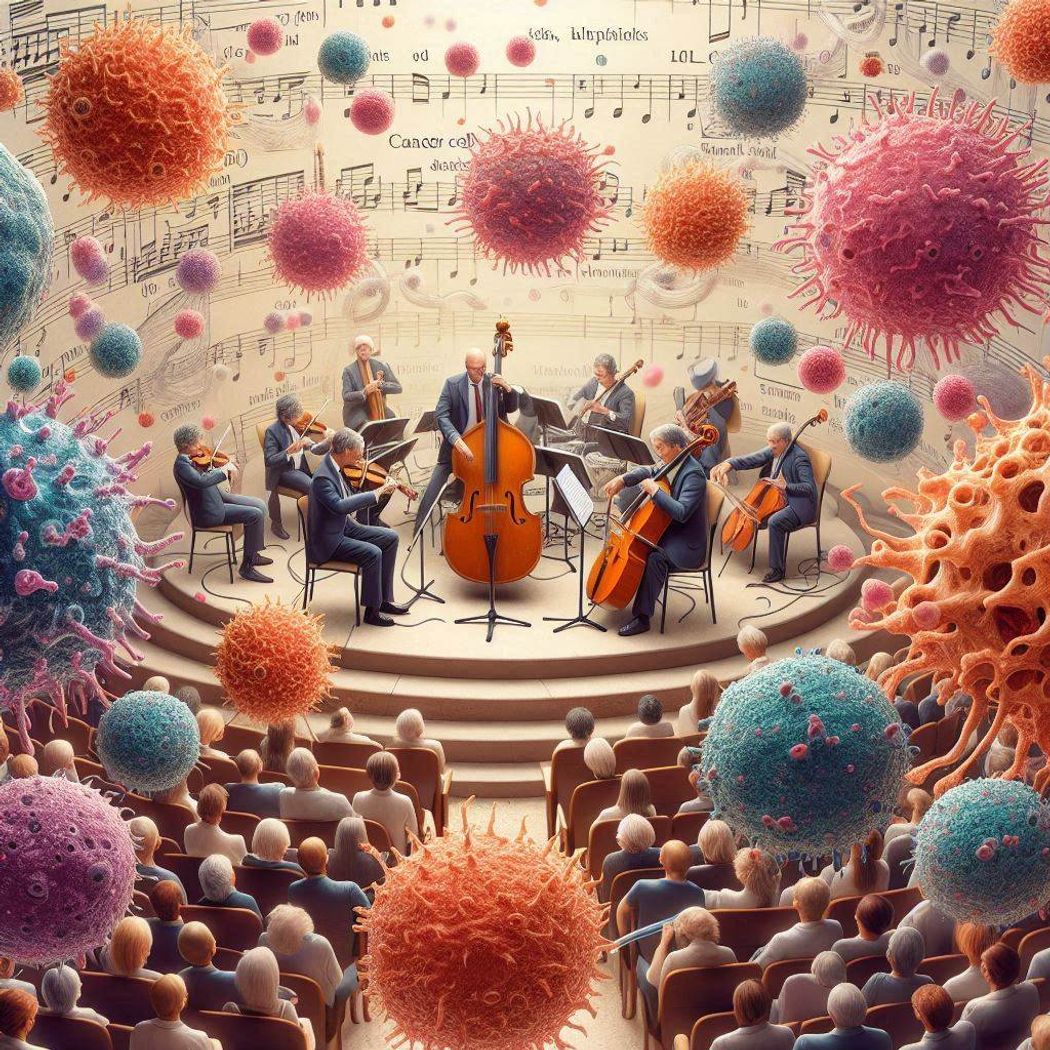

The tumor microenvironment, a complex and discrete system akin to a symphony, features individual cellular components—particularly immune cells—that work together to orchestrate defenses against resident tumor cells.

Chih-Hao Chang, Generated using DALL-E 3 by Microsoft Copilot.

While investigating this phenomenon, researchers discovered that basophils, an often-overlooked immune cell type, play a crucial role in mediating CTL antitumor activity.3 T cells activate these innate immune cells, which make up only 0.5 to 1 percent of the white blood cells, to produce a cytokine that enhances CTL function. Their findings, published in Cancer Immunology Research, offer potential targets for enhancing immunotherapy.

“The results remind us: Don’t forget the basophil,” said study author Chih-Hao Chang, a cancer immunologist at The Jackson Laboratory. While most current research and immunotherapeutic strategies focus on other immune cells, such as T or natural killer cells, their findings highlight the importance of basophils in antitumor immunity, he explained.

To investigate the mechanisms behind CTL exhaustion, Chang and his team grafted melanoma tumors onto mice. As the tumors grew, the researchers observed fewer T cells and a reduction in cytokine levels, including interleukin-3 (IL-3), hallmarks of T cell exhaustion. Treating the tumor-bearing mice with IL-3 reduced tumor growth and metastasis. However, antibody depletion of CTLs reversed this effect, emphasizing the role of CTLs in IL-3-mediated tumor control.

To further explore the effect of IL-3 on CTLs, the researchers cultured the cells with and without the cytokine. In both conditions, the cells exhibited similar proliferation, cytokine production, and metabolic patterns, suggesting that IL-3 does not directly influence CTLs. Instead, the cytokine may act through other cell populations.

When Chang and his team cultured CTLs alongside splenocytes—cells from the spleen, an organ with a large population of CTLs—they found that CTLs exhibited enhanced interferon gamma cytokine production and improved survival.

To identify the cells involved in the process, Chang and his team treated CTLs with supernatants from individually cultured splenocytes. They observed that factors secreted by T cells boosted CTL function, pointing to IL-3, a key T cell cytokine, as a potential player. Consistent with this, depleting IL-3 from T cell supernatant reduced its effect on CTLs, confirming that T cell-derived IL-3 enhances CTL activity.

Given their earlier finding that IL-3 acts indirectly on CTL, the team sought to pinpoint the intermediary cells. Using flow cytometry, they isolated splenocyte populations and observed that basophils expressed high levels of IL-3 receptors. When treated with IL-3, basophils released factors that, in turn, enhanced CTL survival and activity. These results suggest that IL-3-activated basophils play a role in enhancing CTL antitumor responses.

“This was not what I originally expected,” said Chang, who had initially thought that B cells, which make up a majority of the splenic cells, may be involved. “We didn’t expect to isolate a very tiny basophil population,” he added.

To explore how IL-3-activated basophils influence CTL activity, Chang and his team performed RNA sequencing on CTLs treated with supernatant from IL-3-exposed basophils. Their analysis pointed to IL-4 signaling as a key pathway influencing CTL function. Depleting IL-4 from the IL-3-exposed basophil supernatant reduced its positive effects on CTLs. Further, IL-3 injections in tumor-bearing mice lacking IL4 had no impact on tumor growth, confirming a cascade whereby T cells release IL-3, which stimulate basophils to secrete IL-4, which in turn modulates CTL antitumor activity.

When Chang and his team examined tumors from patients diagnosed with melanoma, liver, breast, or ovarian cancer, they found that basophil and IL4 expression was positively correlated with patient survival.

“[The study] is pretty interesting,” said Grégory Verdeil, a cancer immunologist at the University of Lausanne, who was not involved in the study. He noted that while elaborate crosstalk between innate and adaptive immune cells is expected, the involvement of basophils came as a surprise. The next step should be to investigate this mechanism in human tissues, he noted. If that holds true, “It’s just injection of a cytokine which can be done in patients pretty easily,” he said.

More work is required to establish this immune crosstalk in humans, agreed Chang. But their observation that basophil and IL4 signatures are correlated in patients hints that the mechanism they discovered in mice and cultured cells likely holds true in humans, he noted. “That little population [of basophils], if we manage to expand or induce in humans, then that could help enhance treatment.”

- Yi M, et al. Exploiting innate immunity for cancer immunotherapy. Mol Cancer. 2023; 22(1):187.

- Chow A, et al. Clinical implications of T cell exhaustion for cancer immunotherapy. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2022;19(12):775-790.

- Wei J, et al. IL3-driven T cell-basophil crosstalk enhances antitumor immunity. Cancer Immunol Res. 2024;12(7):822-839.