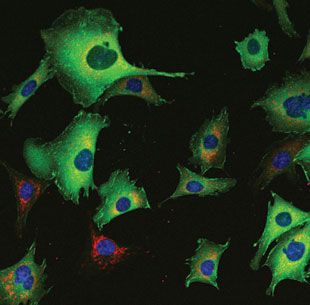

NEXT TO NORMAL: Living cells, such as the CHO-K1 (Chinese Hamster Ovary) cells pictured here, can answer many questions about biology—but only if they’re behaving normally.COURTESY OF CLAIRE M. BROWN, DIRECTOR OF THE MCGILL UNIVERSITY LIFE SCIENCES COMPLEX IMAGING FACILITYCells are at their most natural in a warm, moist, dark environment. Put them in the spotlight on the microscope stage, and they may wither like an ingénue paralyzed by stage fright.

NEXT TO NORMAL: Living cells, such as the CHO-K1 (Chinese Hamster Ovary) cells pictured here, can answer many questions about biology—but only if they’re behaving normally.COURTESY OF CLAIRE M. BROWN, DIRECTOR OF THE MCGILL UNIVERSITY LIFE SCIENCES COMPLEX IMAGING FACILITYCells are at their most natural in a warm, moist, dark environment. Put them in the spotlight on the microscope stage, and they may wither like an ingénue paralyzed by stage fright.

You can’t get rid of the spotlight if you hope to image live cells, but by carefully managing temperature, pH, and humidity, you can make your stars as comfortable as possible—ensuring their onstage chemistry and activities are the same as in the privacy of the incubator.

“Environmental control is one of the most important aspects of live-cell imaging,” says David Spector of Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory in New York, who co-edited the Laboratory’s manual on live-cell imaging. And it’s one with a high payoff, he adds—“A movie is worth a million words.”

If the temperature is off by just a couple of degrees, you aren’t looking at healthy tissues. Cell division ceases, for example, and embryo heartbeats stall. “Cells are used to a pretty controlled environment in vivo,” says Claire Brown, who runs an imaging facility at McGill University in Montreal. “If they’re not in that kind of controlled environment, you don’t know if you’re looking at artifacts.” Mammalian tissues prefer 37 °C, of course, but some control systems can also ...