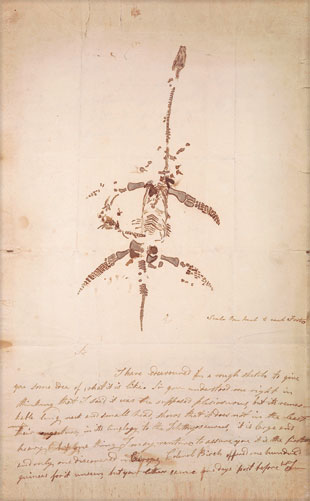

BREAKING THE STRATA: When Mary Anning excavated and reconstructed the first near-complete skeleton of a plesiosaur, she quickly realized she had unearthed something special. Anning drew a detailed sketch of the specimen in this letter, dated December 26, 1823, but never received any official credit for the discovery. WELLCOME COLLECTION, CREATIVE COMMONSAs a working-class woman in 19th-century England, Mary Anning faced stacked odds. Born into poverty in 1799, she received no formal education and quite literally scraped a living from the sea cliffs near her Dorset home, selling whatever fossils she could find. Yet Anning made some spectacular discoveries and taught herself so much that she became an expert paleontologist, contributing as much scientific knowledge about the creatures of the Mesozoic as the most eminent gentlemen geologists of the day.

BREAKING THE STRATA: When Mary Anning excavated and reconstructed the first near-complete skeleton of a plesiosaur, she quickly realized she had unearthed something special. Anning drew a detailed sketch of the specimen in this letter, dated December 26, 1823, but never received any official credit for the discovery. WELLCOME COLLECTION, CREATIVE COMMONSAs a working-class woman in 19th-century England, Mary Anning faced stacked odds. Born into poverty in 1799, she received no formal education and quite literally scraped a living from the sea cliffs near her Dorset home, selling whatever fossils she could find. Yet Anning made some spectacular discoveries and taught herself so much that she became an expert paleontologist, contributing as much scientific knowledge about the creatures of the Mesozoic as the most eminent gentlemen geologists of the day.

“More than anyone else at the time, she showed what extraordinary things could turn up in the fossil record,” says Hugh Torrens, professor emeritus of the history of geology at the University of Keele in the United Kingdom.

Growing up on England’s rocky southern coast, Anning first learned the skills of finding and cleaning up fossils from her father, a cabinetmaker and occasional fossil hunter who sold them as curiosities to tourists. When he died in 1810, the family continued the trade to eke out a meager income. A year later, Mary’s brother found a skull protruding from beneath a cliff, and, slowly, Mary excavated an almost complete skeleton of a long-snouted, dolphin-like reptile, later named Ichthyosaurus, or “fish lizard,” by Henry de la Beche.

...