WIKIPEDIA, NEPHRONAn antidepressant drug appears to deter the formation of amyloid plaques associated with Alzheimer’s disease, according to a study published today (May 14) in Science Translational Medicine. A team led by Yvette Sheline of the University of Pennsylvania studied the effects of citalopram, a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI), on mice and a small group of people.

WIKIPEDIA, NEPHRONAn antidepressant drug appears to deter the formation of amyloid plaques associated with Alzheimer’s disease, according to a study published today (May 14) in Science Translational Medicine. A team led by Yvette Sheline of the University of Pennsylvania studied the effects of citalopram, a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI), on mice and a small group of people.

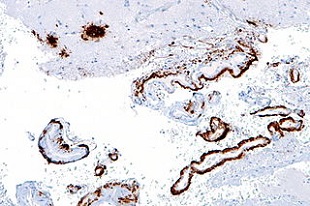

Amyloid plaques and neurofibrillary tangles can be found in the brains of Alzheimer’s patients, but it’s not clear if the plaques are precursors to neurodegenerative problems or an effect of them. Citalopram, which is marketed as Celexa and Cipramil, is typically used to treat depression, anxiety, or obsessive-compulsive disorder. Sheline’s team had previously determined that SSRIs work through serotonin receptors on extracellular receptor kinase. “This results in an up-regulation of alpha-secretase, an enzyme that cleaves amyloid, and therefore reduces its production,” Sheline told The Scientist in an e-mail. “Every SSRI we have tested in mouse models has the same effect on lowering amyloid concentrations.”

The researchers first studied the effects of citalopram in the brains of mice. Using a technique developed by study coauthor Jin-Moo ...