Humans have been tinkering with ways to ferment milk into more shelf-stable products like kefir, cheese, and yogurt for thousands of years. Today, even though most commercially produced yogurt depends on standardized microbial cultures, various communities still rely on traditional practices like adding nettle roots, green chillis, or pinecones to warm milk.1

Perhaps the most intriguing among these is the Turkish and Bulgarian practice of making ant yogurt using the adult insects or their larvae as starters. In a new study published in iScience, researchers identified the bacteria, acids, and enzymes in ants that enable fermentation of milk into yogurt.2 These findings highlight the biodiversity embodied in traditional yogurts, which can include multiple species and strains, as opposed to the simplified modern ways.

“Today’s yogurts are typically made with just two bacterial strains,” said Leonie Jahn, a microbiologist at the Technical University of Denmark and coauthor of the study, in a statement. “If you look at traditional yogurt, you have much bigger biodiversity, varying based on location, households, and season. That brings more flavors, textures, and personality.”

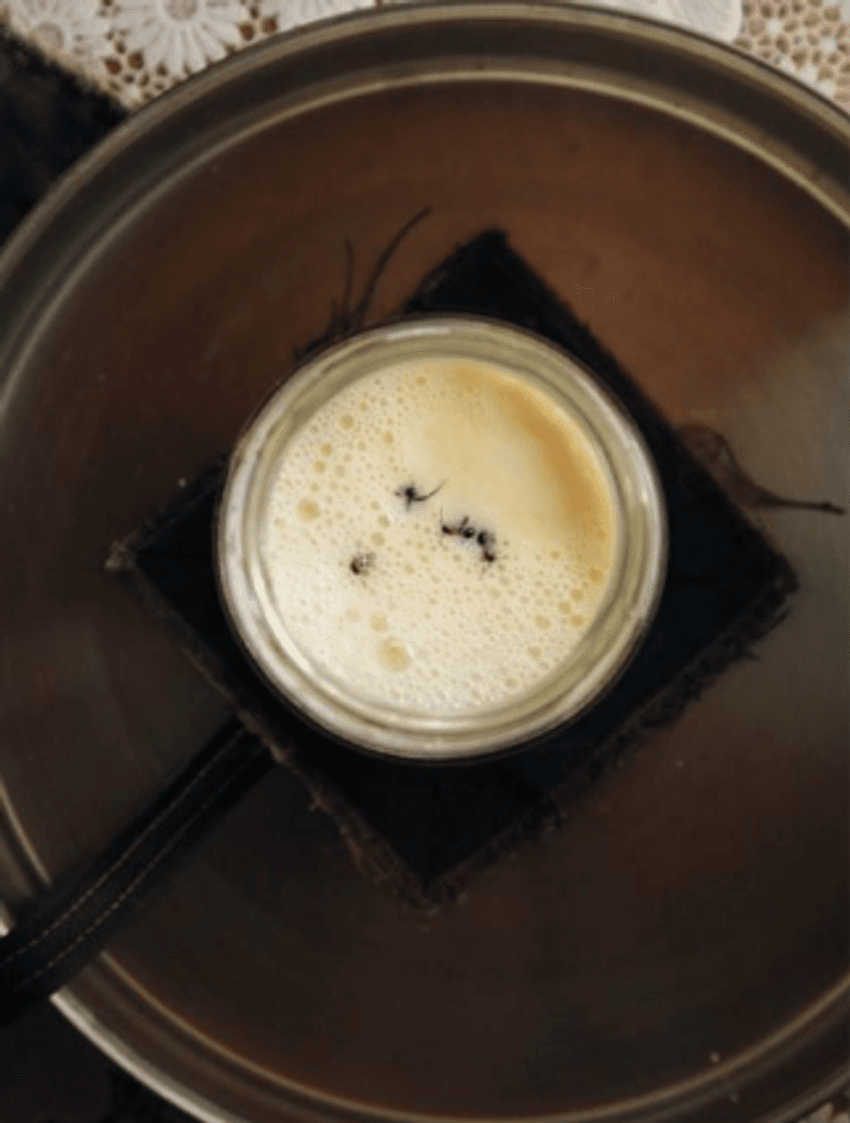

Researchers added four live forest ants to a jar of warm milk to produce ant yogurt, reviving a traditional Balkan recipe. The microbes, acids, and enzymes in the insects and their associated bacteria facilitate the process.

David Zilber

To study how ants turn milk into yogurt, Jahn and her team worked with members of a community in Bulgaria that retained an oral history of the practice. Based on traditional knowledge, the researchers selected the ant species Frutilactobacillus rufa to make yogurt. They added four live ants to a jar of warm milk and left the container to ferment overnight within the ant colony. The next day, Jahn and her team observed that the milk had coagulated, become acidic, and tasted tangy—all indicative of yogurt formation.

The scientists hypothesized that the ant holobiont, which consists of the insect and the microbes living in and on it, contribute to milk fermentation. To test this, they characterized the bacterial microbiome of two red ant species, F. rufa and F. polyctena. Lactic acid bacteria (Lactobacillaceae), acetic acid bacteria (Acetobacteraceae), and obligate intracellular bacteria (Anaplasmataceae) dominated the microbiome of these ants. Since lactic acid is a key product of milk fermentation, Jahn and her team speculated that the bacteria present in the ant microbiome could aid the production of yogurt. Upon adding F. polyctena to milk under sterile conditions, the team found the ant holobiont bacterial species in the fermented product.

The most prominent bacterial genus in the ant yogurt was Fructilactobacillus, from which the team isolated F. sanfranciscensis, a species associated with ants and with sourdough bread fermentation. The team tested the metabolic potential of the bacteria and observed that they could rapidly catabolize various sugars found in milk to produce lactic acid.

Communities in Turkey and Bulgaria have relied on traditional practices of making yogurt, by adding live ants to warm milk and incubating it within the ant colony.

David Zilber

However, ants themselves also produce acids, which they use for defensive behaviors. Jahn and her colleagues analyzed the various acids present in ant yogurt using high-performance liquid chromatography and detected lactic, acetic, and formic acid, among which the most abundant one was the ant-produced formic acid. The team speculated that the unconventional mixture of these acids most likely imparted a unique flavor and texture to the yogurt.

Though the researchers successfully made ant yogurt, they noticed a peculiarity about the process. Typically, yogurt formation needs a low pH of 4.6, which facilitates the aggregation of protein. However, while ant yogurt does not reach this level of acidity, it firms up. Jahn and the team looked for other factors that might modify the texture of ant yogurt, such as enzymes from the ant holobiont. They conducted a proteomic analysis of the insects, ant yogurt bacteria, conventional yogurt bacteria, and milk proteins and observed that the ants and their associated bacteria contributed proteases and peptidases to the yogurt fermentation. Key among these was an ATP-dependent protease capable of cleaving casein, the main protein in milk, to produce yogurt and impart texture.

Researchers added live ants to milk, creating a traditional yogurt that tastes tangier than commercial varieties.

David Zilber

Finally, the researchers collaborated with Michelin star chefs to make various foods using the ant yogurt: an ice cream sandwich or an “ant-wich,” mascarpone-like cheese with a pungent flavor, and a milk-washed cocktail. Despite the culinary potential of ant yogurt, the authors cautioned against the general use of this method since ants could carry harmful pathogens.

“Giving scientific evidence that these traditions have a deep meaning and purpose, even though they might seem strange or more like a myth, I think that’s really beautiful,” Jahn said.

Veronica Sinotte, a microbial ecologist at the University of Copenhagen and coauthor of the study, said, “I hope people recognize the importance of community and maybe listen a little closer when their grandmother shares a recipe or memory that seems unusual.” She added, “Learning from these practices and creating space for biocultural heritage in our foodways is important.”

- Sirakova SM. Forgotten Stories of Yogurt: Cultivating Multispecies Wisdom. J Ethnobiol. 2023; 43, 250–261.

- Sinotte VM, et al. Making yogurt with the ant holobiont uncovers bacteria, acids, and enzymes for food fermentation. iScience. 2024.