When Italian astronomer Giovanni Schiaparelli peered at Mars through a powerful telescope in the late 1800s, he observed dark channels raked across its surface. These features became the key characteristics in his detailed maps of the planet, which fueled more than a decade of wild speculation regarding alien-built canals.

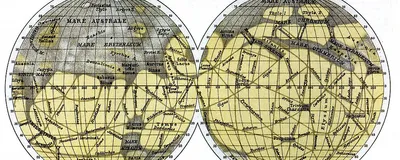

Schiaparelli’s drawings were provocative. His first detailed map of Mars, published in 1877, laid out an intricate network of channels (or canali in Italian) that were colored in blue, in sharp contrast to other representations at the time that marked the Martian surface in the reddish-orange shades that more closely approximate the planet’s actual hue. His later diagrams became more abstract—winding waterways became straight, dark lines—partly in response to criticism from other astronomers, says Maria Lane, a historical geographer at the University of New Mexico who wrote Geographies of Mars, a book about Schiaparelli’s and others’ maps.

These 19th-century diagrams set ...