As microbes invade the human body, phagocytic cells such as macrophages spring into action to clear the intruders. These cells extend arm-like projections and wrap them around the microbes before sealing them in vesicles for degradation.

This process of phagocytosis is critical for eliminating pathogens, but researchers do not fully understand the fate of phagocytosed microbes. “Certain phagocytes [can] extract antigens from the vesicles that contain the pathogens, to present those antigens to T cells,” said Johan Garaude, an immunologist at the National Institute of Health and Medical Research (INSERM). “I was wondering whether the content of those vesicles could also serve the macrophage metabolism.”

Now, Garaude and his team have found that macrophages salvage nutrients from phagocytosed bacteria to support their energy requirements, and that this metabolic recycling differs between dead and live bacteria.1 Their results, published in Nature, provide a deeper understanding of host-pathogen interactions and offer potential therapeutic targets against bacterial infections.

Bacteria hijack nutrients during an infection, explained Garaude. “In order to compensate [for] this lack of nutrients, macrophages probably have developed this capacity so they can feed themselves with the phagocytosed bacteria.”

“This is a very good, comprehensive study,” said Andrea Wolf, an innate immunologist at Cedars-Sinai Medical Center who was not involved in the study. She noted, “Evolutionarily, the process of phagocytosis is a nutrient acquisition method,” which single-celled organisms like amoebas rely on. “[So,] I'm not terribly surprised about that.”

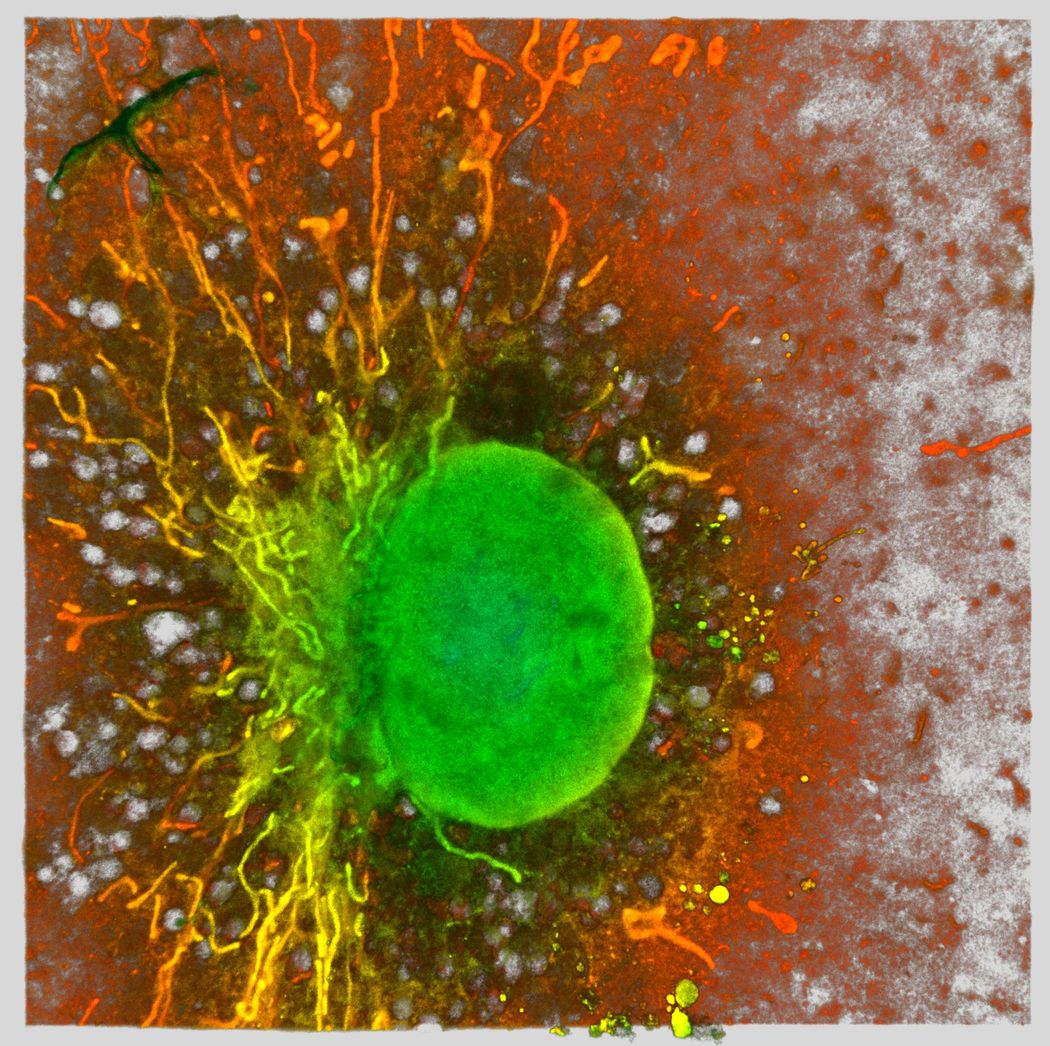

Macrophages use ingested bacteria to fuel the mitochondrion. Using expansion microscopy, researchers captured the mitochondrial network (fibrillate structures) and nuclei (green round structure) of a murine macrophage.

Mónica Fernández Monreal, University of Bordeaux

Garaude and his team started by treating cultured macrophages with killed Escherichia coli cells. This resulted in increased expression of mitochondrial genes associated with ion transport. They also observed an elevated oxygen consumption rate, suggesting that phagocytosis of bacteria fuels the mitochondrial respiratory chain.

To trace the fate of phagocytosed bacteria, Garaude and his team exposed cultured macrophages to dead E. coli that had metabolites labeled with a heavy isotope of carbon. Using mass spectrometry, the researchers tracked the heavy carbon atoms to several macrophage metabolites, including antioxidant and anti-inflammatory molecules like glutathione, indicating that ingested bacteria provide metabolic intermediates.

When the researchers injected labeled, killed E. coli into mice and isolated macrophages, they observed that some metabolites contained heavy carbon, revealing that phagocytes metabolically recycle engulfed bacteria in vivo.

The team hypothesized that the mechanistic target of rapamycin complex 1 (mTORC1) pathway, which activates metabolite synthesis, would regulate this microbe-derived nutrient recycling.2 To test the involvement of mTORC1, the researchers either blocked or activated the pathway in macrophages. They then let these cells engulf labeled, killed bacteria and traced the fate of the metabolites. They observed that phagocytosis by macrophages with blocked mTORC1 resulted in more catabolism of bacterially-derived nutrients and higher concentrations of glutathione pathway products. Activating the pathway in macrophages resulted in the opposite effects, establishing that mTORC1 regulates nutrient recycling of ingested microbes.

Garaude and his team next investigated whether this cascade differed in live and dead bacteria. Metabolomic analyses revealed that, compared to the phagocytosis of live bacteria, macrophages that engulfed dead microbes had increased production of antioxidants and an immunomodulatory metabolite.

“The fact that handling of the molecules was different according to the viability of the bacteria…was actually quite surprising to us,” said Garaude.

The team found that, unlike live bacteria, dead bacteria contained 3′,5′-cyclic adenosine monophosphate (cAMP) and released a byproduct of this metabolite upon phagocytosis by macrophages. This in turn resulted in a cascade that inhibited mTORC1, leading to increased antioxidant responses via glutathione pathway metabolites, eventually blocking pro-inflammatory responses.

“I'm not surprised that there were differences [between live and dead bacteria],” said Wolf. “I wonder if they're really differences in recognition or differences in timing.” She explained that live bacteria may employ mechanisms to slow down the processes that will ultimately mirror what dead bacteria do. She noted that future work should investigate whether researchers can tap into the phagocytic responses to dampen inflammation.

“[The results] actually open a new way to see how metabolism could be important to fight bacterial infection,” said Garaude. “It’s a new avenue that we have to explore a little bit further how we can actually control this phenomenon to fight bacterial infection.”

- Lesbats J, et al. Macrophages recycle phagocytosed bacteria to fuel immunometabolic responses. Nature. 2025;640(8058):524-533.

- Efeyan A, et al. Nutrient-sensing mechanisms and pathways. Nature. 2015;517(7534):302-310.