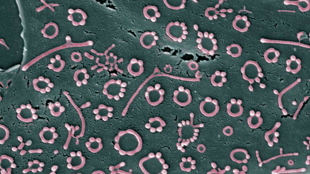

FLICKR, KEVIN MACKENZIE, UNIVERSITY OF ABERDEENResearchers at King’s College London were working on some human gene expression experiments in 2008 when they got a strong match to one of the probe sequences in an Affymetrix microarray. The only available information on the gene from the chip was that it was a human sequence, recalled William Langdon, who helped on the project. So the team did a BLAST search to look up more information. “And the first thing you get back is, of course, the human sequence itself,” said Langdon, who is now at University College London. But when he scanned down the list of the other related sequences that appeared in the search, it was apparent something was amiss. “They [were] all different species of Mycoplasma.”

FLICKR, KEVIN MACKENZIE, UNIVERSITY OF ABERDEENResearchers at King’s College London were working on some human gene expression experiments in 2008 when they got a strong match to one of the probe sequences in an Affymetrix microarray. The only available information on the gene from the chip was that it was a human sequence, recalled William Langdon, who helped on the project. So the team did a BLAST search to look up more information. “And the first thing you get back is, of course, the human sequence itself,” said Langdon, who is now at University College London. But when he scanned down the list of the other related sequences that appeared in the search, it was apparent something was amiss. “They [were] all different species of Mycoplasma.”

It appeared a case of mistaken identity; the original submitter of the sequence to GenBank must have had Mycoplasma contamination in a human sample, and assumed the sequence was human. In a study Langdon and colleagues published in 2009, the authors show the striking resembling between this “human” sequence and a particular marker sequence from various Mycoplasma species.

To this day, the sequence is still labeled “Homo sapiens unknown” in the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) database Genbank. This misnomer represents one of the hundreds—perhaps thousands—of sequences deposited to GenBank and elsewhere that have been assigned to the wrong taxon.

That errors exist in GenBank and other databases is a truism. But correcting mislabeled sequences is a difficult task, one that database stewards and ...