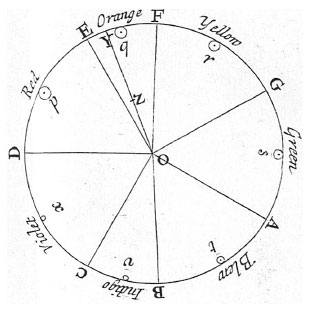

COLOR NOTES: In Newton’s color wheel, in which the colors are arranged clockwise in the order they appear in the rainbow, each “spoke” of the wheel is assigned a letter. These letters correspond to the notes of the musical scale (in this case—the Dorian mode—the scale starts on D with no sharps or flats). Newton devised this color-music analogy because he thought that the color violet was a kind of recurrence of the color red in the same way that musical notes recur octaves apart. He introduced orange and indigo at the points in the scale where half steps occur: between E and F (orange) and B and C (indigo) to complete the octave.ISAAK NEWTON, WIKIMEDIA COMMONSAround 1665, when Isaac Newton first passed white light through a prism and watched it fan out into a rainbow, he identified seven constituent colors—red, orange, yellow, green, blue, indigo, and violet—not necessarily because that’s how many hues he saw, but because he thought that the colors of the rainbow were analogous to the notes of the musical scale.

COLOR NOTES: In Newton’s color wheel, in which the colors are arranged clockwise in the order they appear in the rainbow, each “spoke” of the wheel is assigned a letter. These letters correspond to the notes of the musical scale (in this case—the Dorian mode—the scale starts on D with no sharps or flats). Newton devised this color-music analogy because he thought that the color violet was a kind of recurrence of the color red in the same way that musical notes recur octaves apart. He introduced orange and indigo at the points in the scale where half steps occur: between E and F (orange) and B and C (indigo) to complete the octave.ISAAK NEWTON, WIKIMEDIA COMMONSAround 1665, when Isaac Newton first passed white light through a prism and watched it fan out into a rainbow, he identified seven constituent colors—red, orange, yellow, green, blue, indigo, and violet—not necessarily because that’s how many hues he saw, but because he thought that the colors of the rainbow were analogous to the notes of the musical scale.

Naming seven colors to correspond to seven notes is “a kind of very strange and interesting thing for him to have done,” says Peter Pesic, physicist, pianist, and author of the 2014 book Music and the Making of Modern Science. “It has no justification in experiment exactly; it just represents something that he’s imposing upon the color spectrum by analogy with music.”

Of his rainbow experiment Newton wrote that he had projected white light through a prism onto a wall and had a friend mark the boundaries between the colors, which Newton then named. In his diagrams, which showed how colors corresponded to notes, Newton introduced two colors—orange and indigo—corresponding to half steps in the octatonic scale. Whether Newton’s friend delineated indigo and orange on ...