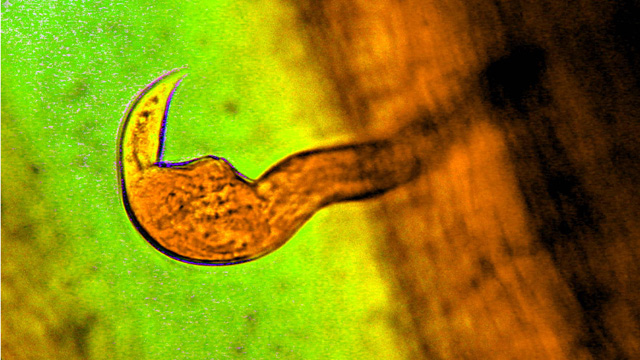

FLICKR, JWINFRED

FLICKR, JWINFRED

Any given mammalian immune system mixes it up with trillions of individual microorganisms, viruses, and macroparasites on a regular basis. These foreign invaders can cooperate with each other to create conditions favorable for the colonization of their host. University of Bourgogne evolutionary ecologist and Faculty of 1000 Member, Gabriele Sorci, discusses a paper that describes how parasitic worms may make it easier for some bacteria to infect the same host in the wild (The American Naturalist, 176:613-24, 2010).

Gabriele Sorci: Helminths are believed to activate the T-helper type 2 immune response. This type of response is characterized by the production of anti- inflammatory cytokines which reduce the amount of proinflammatory cytokines, needed to fight microparasite infections such as viruses or intracellular bacteria. This picture is ...