Antibiotic resistance is a major public health issue, so researchers are constantly looking for new solutions to tackle this problem. Two candidates with bactericidal properties that are not traditional antibiotic molecules have gained traction: bacteriophages and silver nanoparticles.

Damayanti Bagchi is a material chemist who led the study on the development of bactericidal phage-silver nanoparticle conjugates. At the time, she was a postdoctoral researcher in molecular biologist Irene Chen’s laboratory at the University of California, Los Angeles.

Damayanti Bagchi

In a recent study, researchers wanted to “take advantage of both worlds,” said Damayanti Bagchi, a material chemist who led the work as a postdoctoral researcher in Irene Chen's laboratory at the University of California, Los Angeles.1 For the first time, Bagchi and her colleagues synthesized silver nanoparticles using phages called M13, which they also used as a scaffold for the nanoparticles. The silver particle and M13 phage conjugate killed bacteria more effectively than each component alone. The conjugate also slowed down the development of bacterial resistance. This work, published in Langmuir, expands researchers’ arsenal of weapons in their fight against antibiotic resistance.

“This is quite new, using phages as scaffolds [for silver nanoparticles]. I find it very exciting,” said Timea Fernandez, a biochemist at Winthrop University who was not involved in the study.

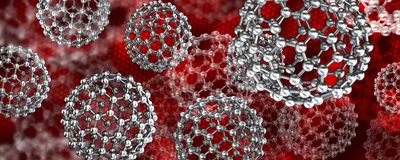

To make silver nanoparticles, researchers must reduce silver ions to neutral, metallic silver so they can form clusters. They then perform a “capping” reaction to stabilize the clusters once they reach a desired size to prevent them from aggregating. Traditionally, researchers have relied on chemical reagents such as sodium borohydride and citrate for these steps, but environmental concerns have compelled them to consider sourcing their reagents from the natural world. So, some researchers use plant extracts as well as phages, such as M13, to reduce and cap silver.2,3

In the present study, Bagchi and her colleagues synthesized silver nanoparticles using the M13 phage. Because cellular toxicity is a common concern associated with silver nanoparticles, the team wondered if they could lower the dose of nanoparticles needed to kill bacteria by administering them alongside phages.

The researchers discovered that silver nanoparticles synthesized and scaffolded using M13 phages were about 30 times more potent than their commercial silver nanoparticle counterparts. The amount of phage-silver nanoparticle conjugate needed to kill bacteria was more than 10 times lower than the amount of silver nanoparticles that caused noticeable toxicity in human cells. The researchers also observed that bacterial resistance against the conjugate developed more slowly than against the silver nanoparticles alone.

“The most surprising [thing] to me was that the conjugate is what’s responsible for this effect,” Bagchi said. She had expected that the silver nanoparticle would be the magic bullet, but when the team treated the conjugate with acid to dissolve the phage, the nanoparticles’ bactericidal effects were nowhere near their conjugated counterparts. “It’s the conjugate that makes it special—that's a very new thing that we found,” Bagchi added.

The technique’s novelty impressed Fernandez, though she noted that a different group had published a similar study about a month earlier.4 “What I really liked about this paper is they really took a deep dive in identifying the molecular details,” she said, referring to mutagenesis experiments that the researchers performed to identify the specific amino acid residues on the phage that were vital for the nanoparticle synthesis. “It’s admirable for something that’s reasonably new,” Fernandez added. “They did a very well-rounded, very thorough work.”

Though Bagchi is no longer involved in the project, she shared that the team is now testing their findings in mice. Fernandez thinks that researchers must ensure that the conjugates do not accumulate in the internal organs or harm the microbiome before they can be administered into humans.

“It will be a future systemic drug, but it needs much more study,” Bagchi said.

- Bagchi D, et al. Silver nanoparticles templated by M13 phage exhibit high antibacterial activity against gram-negative pathogens and reduced rate of bacterial resistance in vitro. Langmuir. 2025.

- Asif M, et al. Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles (AgNPs), structural characterization, and their antibacterial potential. Dose Response. 2022;20(1):15593258221088709.

- Nam KT, et al. Peptide-mediated reduction of silver ions on engineered biological scaffolds. ACS Nano. 2008;2(7):1480-1486.

- De Plano LM, et al. Engineered phage-silver nanoparticle complexes as a new tool for targeted therapies. Sci Rep. 2025;15(1):36135.